| Laws cannot say exactly what people must do. Lighting

laws, regulations and standards only set reasonable lower limits on required

equipment and its performance. Equipment which exceeds the requirements should be

permitted in order to encourage development of improved products, and to permit bicyclists

to use their own discretion.

A law specifying required equipment too narrowly or requiring non-essential equipment has little effect in reducing accident rates, but risks a bicyclist's being held at fault -- and not collecting on insurance -- in an accident resulting from a violation by someone else, even though the bicyclist could be seen (or could have been seen if the violator was looking). What the traffic law should requireThe traffic law should require a white headlight, and a bright, amber or red rear reflector and/or taillight, with specified, adequate performance. Every state in the U.S. unreasonably narrows the types of equipment permitted (for example, by outlawing an amber rear reflector, or by requiring pedal reflectors while prohibiting ankle bands.) Many states require non-essential equipment, and some states require equipment which is technically flawed. Bicyclists' organizations propose revisions to the laws from time to time. You might consider becoming involved in this effort. About standards for equipment and for its marketingState laws generally specify that lights or reflectors must be visible from a certain

distance. This requirement is not technically precise. Even a lighted match is visible

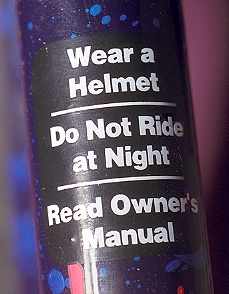

from half a mile away in complete darkness. Meaningful performance standards must be based

on laboratory measurements. As should be clear from previous pages, the Federal requirement for equipment on new bicycles is deeply flawed. While an international standard does exist, many lights have been sold in the U.S. which do not meet it. The reflector specification also needs a major overhaul, to the extent that some manufacturers are now plastering "do not ride at night" stickers onto bicycles which have the Federally-required nighttime equipment. The stickers began appearing after a bicyclist was permanently disabled in a collision with a motorist who could not see his front reflector, and won a multi-million dollar jury award. John Forester, the plaintiff's expert in that case, has posted information about the case (Johnson v. Derby) on his Web site along with additional information about lighting laws and regulations. See also Dr. Ross Petty's analysis of the effect of the CPSC regulations. Petty concludes that they have not been effective in preventing crashes. If public opinion about riding at night is determined by accident statistics which are inflated by the use of inappropriate equipment and confused messages, the concept of a bicycle as a practical means of transportation is in trouble. It would also be helpful if government and industry could eliminate the promotion of products in ways which confuse the public. An example of a misleading promotion is discussed elsewhere on this Web site. There is a need for a Federal regulation requiring powerful LED bicycle headlights to have a shaped beam pattern like motor-vehicle headlights, so they do not blind oncoming bicyclists and motorists with glare. Such headlights are manufactured, and available for sale, but others with a round, flashlight-like beam pattern also are sold. Standardization of mounting hardwareAnother important improvement would be standardization of mounting hardware for nighttime equipment. Reflector mounting is largely standardized, and Europe now has a standard mounting system for taillights as well. However, there is no standard in the United States for mounting lights. Adoption of such a standard would require cooperation between industry, standards-setting organizations and government. Next: some unusual reflector photos. |