On March 14, 2011, I attended a meeting in Brookline, Massachusetts, a suburb of Boston. At that meeting, Dr. Peter Furth of Northeastern University, and some of his students, gave a presentation on proposals for street reconstruction and bikeways in the southern part of Brookline.

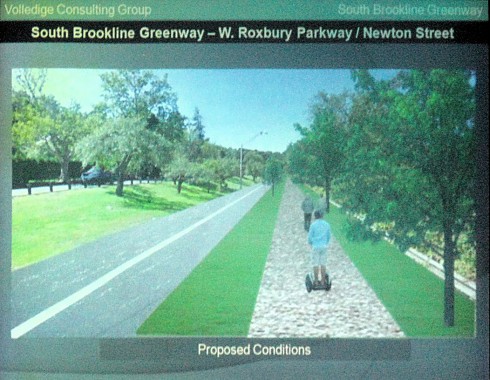

Proposed replacement of two two-lane one-way roadways with shoulders by a narrowed two-way roadway without shoulders and an adjacent multi-use path; Newton Street (up the embankment at the left) to provide local access only.

Most of the streets in the project area are fine for reasonably competent adult and teen cyclists to share with motorists, though one street, Hammond Street, is much less so, with its heavy traffic, four narrow lanes and no shoulders. I do agree with a premise of the presentation, that bicycling conditions could be improved, but I suggest different treatments, such as conversion from four lanes to three, with a center turn lane which becomes a median at crosswalks, also freeing up room at the sides of the roadway for motorists to overtake bicyclists.

Please read through this introduction before looking through the photo album I have posted with images from the meeting presentation, and drawings which were taped up in the meeting room.

My Concerns with the Proposal

Generally, I am concerned with the hazards and delays — and in winter, complete lack of service — which the proposal introduces for bicyclists, and with the blockages and longer trips it introduces for motorists, resulting in delay and in increased fuel use and air pollution. Some specifics:

- The proposed system of narrow two-lane streets and segregation of bicyclists onto parallel paths makes no provision for the foreseeable increasing diversity of vehicle types and speeds as fuel prices rise. This trend can only be managed efficiently and flexibly with streets that are wide enough to allow overtaking.

- Proposed paths are on the opposite side of the street from most trip generators, and many movements would require bicyclists to travel in crosswalks, imposing delay, inconvenience and risk for bicycle travel on the proposed route and on others which cross it. Small children would not safely be able to use the proposed routes unless accompanied by an adult, same as at present.

- The proposal would further degrade or eliminate bicycle access in winter, because of the proposed 22-foot roadway width, and because the proposed parallel paths could not be kept ice-free even if they are plowed.

- Though intersections are key to maintaining traffic flow, the proposal puts forward an incomplete design for most intersections and no design for some of them.

- The narrowed streets provide no accommodation for a vehicle which must stop while preparing to turn left into a driveway, or to make a delivery, or to pick up or discharge passengers, for bicyclists who must travel in the street to reach a destination on the side opposite the path, or for bicyclists who wish to travel faster than the path allows.

- The proposal includes no discussion of improvements to public transportation, which would be key to reductions in congestion and fossil fuel use. There are no bus turnouts, although Clyde and Lee Streets are on an MBTA bus line, school buses use the streets in the project area, and additional bus routes are foreseeable.

- The proposal includes a 12-foot-wide service road along Clyde and Lee Street, part of which is to carry two-way motor traffic along with bicycle and pedestrian traffic. At times of heavy use, 12 feet on the Minuteman Bikeway in Boston’s northwestern suburbs is inadequate with only pedestrian and bicycle traffic. 12 feet is not wide enough to allow one motor vehicle to pass another. Larger service vehicles (moving vans, garbage trucks etc.) could access parts of this service road only by backing in, or by driving up a curb and across landscaped areas. These vehicles would completely block other motorized traffic on the service road.

- The proposal is expensive because it requires tearing up every one of the streets in order to narrow it, not only construction of a parallel path.

Confusion in the Presentation

There also was confusion in the presentation:

- North is confused with south, or east with west in the captions to several photos. Due to the confusion, some photos show a path on the opposite side of the street from where the plan drawings place it.

- Some items in the illustrations are out of proportion. In one illustration (the one near the top in this post), a two-lane arterial street is only 10 feet wide, based on the height of a Segway rider on an adjacent path, or else the Segway rider is 12 feet tall, riding a giant Segway.

- Other details are inconsistent, for example, showing a sidewalk in a plan drawing, but no sidewalk in an image illustrating the same location.

- There is confusion about location of some of the photos. Some cross-section drawings are shown without identification of the location in the plans. The location of one cross section is misidentified.

- The proposal makes unsupportable claims about safety.

There also is an ethical issue: in their presentation, the students have appropriated a number of Google Street View images without attribution — a violation of copyright and of academic ethics. (Furth’s students also plagiarized photos from my own Web site for a different presentation, but I digress.)

Overview and Conclusions

The proposal generally attempts to make bicycle travel a safe option for children and for people who are new to bicycling. It fails to accomplish that, due to problems with access across streets to the proposed pathways. It also adds complication and delay for motorists and for the majority of existing and foreseeable bicycle users. It degrades and sometimes eliminates bicycling as an option in the winter months, and it pays no attention whatever to public transportation.

I have no objection to construction of a path in the parkland adjacent to the streets in the project area, but the proposal also works to enforce the use of the path by reducing the utility of the road network for bicyclists as well as for other users.

I do think that street improvements are desirable, and on one street (Hammond Street) a high priority to improve bicycling conditions, but these improvements can be achieved mostly through restriping, without the massive reconstruction, or rather, deconstruction, that has been proposed. This narrowing the roadways is intended to increase greenspace, and also apparently to reduce speeding, but the proposal goes way overboard in reducing capacity, convenience and flexibility. There are other options to reduce speeding, most notably enforcement and traffic-calming measures which affect speed without decreasing capacity.

The large multi-way rotary intersection of Hammond, Lagrange and Newton Streets, West Roxbury Parkway and Hammond Pond Parkway is the one place where I consider reconstruction to be a high priority.

Education also is an essential element of any attempt to make bicycling safer and a more practical option.

Larger Contextual Issues

Long-run issues of energy cost and availability raise questions about the viability of sprawled suburbs whose residents are dependent on private motor-vehicle travel.

South Brookline is more fortunate. It is a medium-density residential area of single-family homes, only about 5 miles from the Boston city center and also only a few miles from the Route 128 corridor, a major employment concentrator. Schools, places of worship, parklands and shopping are closer than that. Bicycling can and should have a role here, but for many people and many trips, it is not an option, due to age, infirmity, distance, and the need to transport passengers and goods.

South Brookline could benefit from a comprehensive transportation plan, including strengthening of public-transportation options and maintaining arterial roads with capacity for varied existing, foreseeable and unforeseen uses.

Developing such a plan requires skills, resources and time beyond what I can muster, and so I’ll not attempt that here.

Now, please move onto the photo album.

“. . . makes no provision for the foreseeable increasing diversity of vehicle types and speeds as fuel prices rise.”

Like this? http://youtu.be/pERPqJ5J7DU

I look forward to Professor Furth’s and his students’ responses.

Velomobiles as shown in the video are one possibility among many. Others: motor scooters, electrically-assisted bicycles, electrically- or gasoline-powered “golf cars”, pedicabs, bakfiets, cargo bikes. All of these are slower than conventional motor vehicles and some are faster than typical bicyclists’ speed; some are larger than bicycles. These problems are already manifest in Copenhagen (bakfiets and cargo bikes, mostly), Amsterdam (light motorcycles on the sidepaths; New York (pedicabs not allowed in the barrier-separated bikeways) and Tucson (motor scooters on paths), probably other places as well. Faster bicyclists, whether faster due to slope or to strength, also are a problem on paths. All of the slower vehicle types have to be able to reach the speed of which they are capable, rather than to be slowed by mixing with pedestrians, cramming them onto facilities of inadequate width, or, also, on roads, congestion and unfavorable traffic-signal timing. The typical bicycle trip in Amsterdam or Copenhagen is a couple of kilometers. That won’t count for much in the USA where distances to important destinations are larger thanks (or no thanks) to the expanse of land on which to build, and to our cities’ having grown up in the age of the railroad, streetcar and automobile.