Ohio cyclist Patricia Kovacs posted an e-mail asking some questions about roundabouts:

Ohio engineers are telling us to use the inner lane for left turns and U turns. Both the FHWA [Federal Highway Administration] and videos available on our local MPO [metropolitan planning organization] website say this. I shared this when we asked for updates to Ohio Street Smarts. If the FHWA and MORPC [Mid-Ohio Regional Planning Commission] are wrong, then we need to fix it.

Would you review the 8 minute video on the MORPC website and let me know what I should do? If it’s wrong, I need to ask them to update it. This video was made in Washington and Ohio reused it.

Looking further into the problem, I see a related practical issue with two-lane roundabouts, that the distance between an entrance and the next exit may be inadequate for a lane change. The larger the roundabout, the longer the distance in which to change lanes, but also the higher the speed which vehicles can maintain and so, the longer distance required. I’m not sure how this all works out as a practical matter. Certainly, turning right from the left-hand lane when through traffic is permitted in the right-hand lane is incorrect under the UVC [Uniform Vehicle Code], and results in an obvious conflict and collision potential, but I can also envision a conflict where a driver entering the roundabout does not expect a driver approaching in the inside lane of the roundabout to be merging into the outside lane.

All in all, the safety record of roundabouts is reported as good (though not as good for bicyclists and pedestrians), but I’m wondering to what extent the issues have been subjected to analysis and research. When I look online, I see a lot of roundabout *promotion* as opposed to roundabout *study*. Perhaps we might take off our UVC hats, put on our NCUTCD [National Committee on Uniform Traffic-Control devices] hats, and propose research?

Thanks, Patricia.

This post was getting long, so I’ve placed detailed comments on the Ohio video, and embedded the video, in another post. I’m also working on an additional post giving more examples, and I’ll announce it here when it is ready.

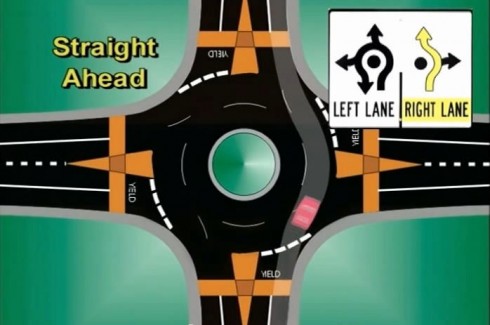

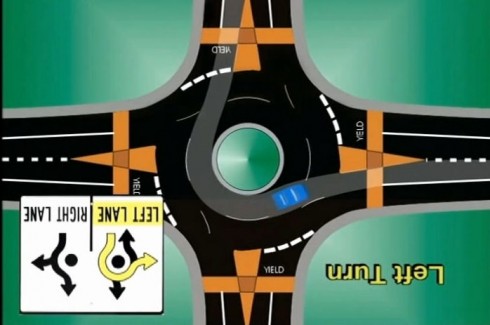

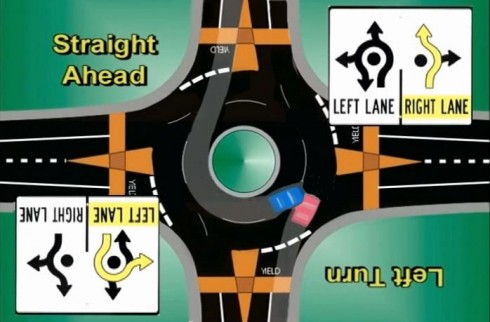

Here are some stills from the video showing the conflict between through traffic in the outer lane and exiting traffic in the inner lane.

First, the path for through traffic:

Next, the path for left-turning traffic:

Now, let’s give that picture a half-turn so the left-turning traffic is entering from the top and exiting from the right:

And combining the two images, here is what we get:

The image below is from the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices, and shows similar but not identical lane use. The arrows in the entry roadways direct through traffic to use either lane.

Drivers are supposed to use their turn signals to indicate that they are to exit from the inner lane — but drivers often forget to use their signals. Safe practice for a driver entering a roundabout, then, is to wait until no traffic is approaching in either lane, even if only entering the outer lane.

A fundamental conceptual issue here is whether the roundabout is to be regarded as a single intersection, or as a series of T intersections wrapped into a circle. To my way of thinking, any circular intersection functions as a series of T intersections, though it functions as a single intersection in relation to the streets which connect to it. Changing lanes inside an intersection is generally prohibited under the traffic law, and so, if a roundabout is regarded as a single intersection, we get the conflicts I’ve described.

Sometimes, dashed lines are used to indicate paths in an intersection, when vehicles coming from a different direction may cross the dashed lines after yielding right of way or on a different signal phase. More commonly, a dashed line indicates that a driver may change lanes starting from either side. The dashed lines in a two-lane roundabout look as though they serve the second of these purposes, though they in fact serve the first. These are shorter dashed lines than generally are used to indicate that lane changes are legal, but most drivers don’t understand the difference.

That leads to confusion. If you think of the roundabout as a single intersection, changing from the inside to the outside lane is illegal anywhere. If you think of the roundabout as a series of T intersections, changing lanes should occur between the entries and exits, not opposite them –though there is also the problem which Patricia mentioned, that a small two-lane roundabout may not have much length between an entry roadway and the next exit roadway to allow for a lane change. That is, however, much less of a problem for bicyclists than for operators of wider and longer vehicles. It would be hard to construct a two-lane roundabout small enough to prevent bicyclists from changing lanes.

My practice when cycling in conventional two-lane traffic circles — and there are many in the Boston, Massachusetts area where I live — is to

- enter from the lane which best leads to my position on the circular roadway — either the right or left lane of a two-lane entry;

- stay in the outer lane if leaving at the first exit;

- control the inner lane if continuing past the first exit;

- change back to the left tire track in the outer lane to prepare to exit.

That way, I avoid conflict with entering and exiting traffic in the outer lane, and I am making my lane change to the right in the slow traffic of the circular roadway rather than on the straightaway following it. This is what I have found to make my interactions with motorists work most smoothly. Why should a bicyclist’s conduct in a roundabout be different?

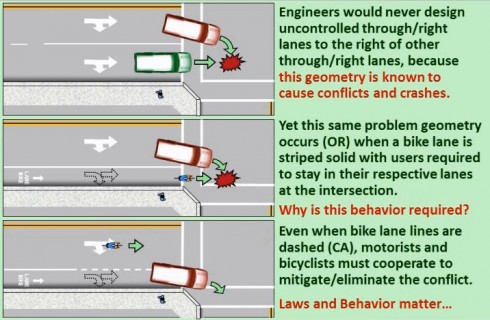

It is usual to be able to turn right into the rightmost lane of a multi-lane roadway while traffic is approaching in the next lane of that roadway. I don’t know of any other examples in road design or traffic law in the USA where a motor vehicle is supposed to turn right across a lane where another motor vehicle is entering. Bike lanes are sometimes brought up to intersections, though the laws of every state except Oregon require motorists to merge into the bike lane before turning. The illustration below, from Dan Gutierrez, depicts the problem.

Applicable sections or the Uniform Vehicle Code are:

- 11:304 (b) — passing on the right is permitted only when the movement can be made in safety.

- 11:308 (c) — a vehicle shall be driven only to the right of a rotary traffic island.

- 11:309 (a) — no changing lanes unless it can be done in safety

- 11:309 (d) — official traffic control devices may prohibit lane changes

- 11:601 (a) Right turns – Both the approach for a right turn and a right turn shall be made as close as practicable to the right-hand curb or edge of the roadway.

For about four years, I’ve lived and driven in England, where roundabouts are ubiquitous. I absolutely agree with your practice of changing to the outside lane before actually exiting. Here’s a satellite view of a roundabout I’m very familiar with (of course the traffic is clockwise this being the left-hand drive country).

It’s an enormous one, right off of one of Europe’s busiest motorways – yet every exit has just one lane. Drivers entering have only one lane of traffic to yield to; this is superior to the confusing American design with two exit lanes. Also, the lanes ‘unwind’ so entering the roundabout via the correct lane (following the direction arrows painted on the tarmac) one often travels in the proper lane throughout even without changing lanes.

Finally, there are signs suggesting that cyclists travel on the outside. Even that is not always comfortable; I went on a ride with fast roadies who used a combination of sidewalks and shortcuts to avoid a large roundabout altogether (staying on the road at all other times).

I’ve noticed that where MassDOT has restriped rotaries as roundabouts, they avoid the crossing paths at the exits issue that these FHWA examples have. As with the FHWA example, you choose your lane prior to entering, and then stay in that lane all the way to your exit. The difference is: if you think of it as a major road intersecting a minor road, MassDOT stripes it so the major road will allow two lanes to enter and exit and the minor road will only have one lane. This eliminates the traffic crossing at the exits issue.

Here are some examples from MA:

Agawam

https://goo.gl/maps/Xpt78

Greenfield

https://goo.gl/maps/peO23

West Springfield

(Check out page 11)

https://web.archive.org/web/20150928050915/http://www.massdot.state.ma.us/Portals/8/docs/HighlightedProjects/memorialAveRotary/Presentation_120214.pdf

There’s more to a modern roundabout than the striping and lane use signs.

Many people confuse other and older styles of circular intersections with modern roundabouts. East coast rotaries, large multi-lane traffic circles (Arc D’Triomphe, Dupont Circle), and small neighborhood traffic circles are not modern roundabouts. If you want to see the difference between a traffic circle, a rotary (UK roundabout) and a modern roundabout (UK continental roundabout), go to https://web.archive.org/web/20150306042525/http://www.k-state.edu/roundabouts/news/Roundabouts.htm to see pictures. And here’s another site that shows the difference between an older rotary and a modern roundabout: https://web.archive.org/web/20150306042525/http://www.k-state.edu/roundabouts/news/Roundabouts.htm [the same page — John Allen]

If any of the entry lanes has a stop sign, it’s not a modern roundabout.

If you could play a game of football in the center landscaped area, it’s not a modern roundabout.

If the circular roadway has a stop sign, yield sign or signal, it’s not a modern roundabout.

If you don’t have to slow down to enter it, it’s not a modern roundabout.

If you have to change lanes in the circular roadway to exit, it’s not a modern roundabout.

If you can easily drive faster than 20 mph in the circular roadway, it’s not a modern roundabout.

If it has a park for pedestrians, or a building, in the middle, it’s not a modern roundabout.

Most modern roundabouts (UK continental roundabouts) have lane use signs before entering (just like with complex signal intersections) that tell you which entry lane can make which movement.

What I didn’t see in the discussion was that yield on entry at a multilane roundabout means yield to both lanes, not just the outside lane if you are entering from a right lane. This would eliminate the approaching from left inside lane exiting to your right crossing conflict that often happens.

The lane change to exit confusion stems mostly from older rotary designs (UK roundabouts), where this was a common practice, and the circular roadways were large.

Passing other vehicles in the circular roadway is also unwise and often prohibited by state law for the same exit/circulating crossing conflict reasons.

Signaling your exit is often required by law, but signaling left until you’re ready to exit will also help motorists not jump in front as you go around. At a multi-lane modern roundabout, like any other multi-lane intersection, motorists should watch for the lane use signs that tell you which lane to be in based on where you want to go. Like other complex intersections, sometimes only the left lane can turn left, sometimes it can turn left and go through, and some times it can go left, through or right.

If you go through all the scenarios of drivers yielding to BOTH lanes on entering the roundabout, and NOT changing lanes in the roundabout, there are no conflicts with drivers exiting from the left (inner) lane. Unfortunately, the signage on the roundabouts in Central Ohio say “Yield to traffic in roundabout”, not “Yield to all lanes in roundabout”. As John noted, most drivers think that they need only yield to traffic in the lane they are entering. There is no sign saying “no passing” and the dashed lines within the roundabout imply that it is OK to change lanes in the roundabout. For all these reasons, the crash rate in the Gahanna, Ohio roundabout had an increase in annual crash rate of 500% over the previous traffic signal. We have finally added bollards to each leg of that roundabout to allow only right turns from the right lane and the crashes have decreased. https://www.google.com/maps/place/1370+E+Johnstown+Rd,+Gahanna,+OH+43230/@40.0532125,-82.8425732,17z/

Also look at with Streetview.

The problem with cyclists becoming pedestrians, or with pedestrians using the crosswalks, is that the yielding behavior of motorists to pedestrians in the crosswalk, particularly at the exit legs of the roundabout are abysmal. I thought it was just a Central Ohio phenomena, but a national study in 2014 found the same problem at other locations in the US.

The study:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3947582/

The terrible numbers:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3947582/table/T3/

In the above chart, aggressive means waiting at the curb edge, passive means waiting approximately 1′ back from the curb edge.

Dan Burden and I observed a pick-up truck driver almost clobber a friend who is blind and her guide dog as she began to enter the crosswalk across the exit leg of the roundabout. I drive my bicycle through the roundabout and have done so before and after the bollards were added. Before the bollards were added, I exited the roundabout from the left (inner) lane by scanning behind and signalling like mad.

I would prefer if the rules for roundabouts were the same as the rules for traffic circles, but unfortunately, the engineers want us to learn something new, so unless I want to be injured and found at fault, I follow the new rules.

Because of the problem with yielding to crosswalks in roundabouts, I advocated for Rectangular Rapid Flash Beacons at 2 new roundabouts being built in Gahanna and they will be added to the crosswalks. I will still drive my bike through the roundabouts but I am hopeful that the RRFB will help with yielding when I am walking. We will wait and see if bollards will be needed.

It’s interesting to see that NHDOT is pretty well exactly implementing figure 3C-6. See https://web.archive.org/web/20150628235315/http://www.fosters.com/article/20150622/NEWS/150629819

I did have to squint for awhile before concluding there is, indeed, no conflict IF entering motorists yield to both lanes. It makes through movements efficient (both lanes can go to the second exit). We’ll see how it goes this summer…I usually go through that intersection weekly. (Car, though. May take a bike trip to try it out.)

This problem has a solution that should work well. Building sidepaths for cyclists, but design them well. With the positioning of the crossings for cyclists between 4 metres, preferably at least 6, up to 10 or more metres, from the right edge of the right lane for motor traffic, built on a hump for motor traffic but is level for cyclists, with clear signage indicating who goes first with clear yield signs and yield markings. At roundabouts, it should be about 10 metres with cyclists yielding, crossing only one lane at a time before arriving at a refuge island at least 2.5 metres wide. If the roundabout is too busy, more than 1750 vehicles per hour an arm, then it should ideally be grade separated, if that is not possible, an unsignalized crossing might work, but probably a small traffic light controlled crossing with low waiting times for cyclists, breaking up traffic. Cyclists have the right of way over side roads if the road it parallels does too. Even if it can’t be 4-10 metres apart all the time, then it should be at intersections, with a wide curve so that slowing down is not needed, even at 40 km/h. In relation to the weaving at multi lane roundabouts, the Dutch have an invention called the turbo roundabout that can help. It uses small ridges, or sometimes even full traffic medians a metre or more wide, to separate the flows by lane, making it so that the problem someone described on multi lane roundabouts never can happen.

I’ve seen a video of a Dutch roundabout with paths around the outside as you describe, the one outside s’Hertogenbosch. YouTube video is here. A major advantage of a roundabout is that traffic can keep moving, but paths around the outside negate that advantage when motorists must yield to pedestrians or bicyclists, and this can back up traffic entering and leaving the roundabout. It works, with Dutch drivers and the traffic calming your describe. As Patricia Kovacs notes, though, US drivers don’t reliably yield, and neither do US roundabouts have the traffic calming features. A particular problem occurs at the exit to the roundabout, where it is often not possible to tell whether a vehicle is going to exit or to continue in the roundabout.

This writeup is very good, and gets to the heart of a lot of the confusion that people have about multi-lane roundabouts. There are a few statements that are not correct, though, that feed into this confusion:

“Drivers are supposed to use their turn signals to indicate that they are to exit from the inner lane”

Actually, this is not true. Drivers should not use a turn signal when exiting a roundabout under typical American designs. The Uniform Vehicle Code requires drivers to use turn signals in advance of a lane departure or to turn onto another roadway. But, exiting a multi-lane roundabout is neither of these. When exiting a multi-lane roundabout, regardless of which lane you are in, you are simply following your lane out of the intersection. Note in the FHWA figure that the pavement arrows indicate that exiting is a through movement, while circulating is a left turn. It could be argued that circulating traffic is required to use their left turn signal, but exiting traffic would not use any signal. In Minnesota, state law specifically states that drivers are not required to use a turn signal at a roundabout. This got into state law because some overzealous officers, confused about roundabouts, were stopping motorists who had not committed any infraction.

“A fundamental conceptual issue here is whether the roundabout is to be regarded as a single intersection, or as a series of T intersections wrapped into a circle. To my way of thinking, any circular intersection functions as a series of T intersections”.

Actually, it is neither of these. A roundabout is best thought of two pairs of one-way roads intersecting each other, creating a total of four individual intersections in a lattice-type pattern. You can certainly choose to think of this set of four intersections as one overall “junction”, much like a freeway interchange can be thought of as one overall junction despite containing numerous different ramp intersections that may be far from each other. But, from an operational perspective, a roundabout functions as four separate intersections. Each of them operates per the standard lane use rules that you would have when two one-way roads intersect each other.

So, for example, a roundabout might consist of a westbound road, an eastbound road, a northbound road, and a southbound road. To traverse the roundabout from the south to head west, you would first cross the eastbound road (after yielding), then make a left turn onto the westbound road, then cross the southbound road (which yields to you). To make the left turn onto the westbound road, you need to be positioned to the left of the northbound through traffic, just like at a standard intersection.

Hope this helps!

Interesting and thoughtful comment, but it raises some questions with me.

Then how does a driver entering the roundabout to use the outer lane know whether it is safe to enter? If the driver circulating in the inner lane is going to continue around, then the other driver can safely enter. If the driver circulating in the inner lane exits, then the entering driver must yield, or there is the risk of a collision. I suppose that the safe bet is never to enter when a vehicle might cross the outer lane, but that does reduce potential throughput.

If there are four two-way roads, then there are four intersections but with the separation of the entrance and exit roadways in a roundabout, then there are 8 T intersections, alternating with one-way entry and exit roadways to/from the circular roadway. I can’t picture the lattice which you describe. Can you point me to a diagram which clarifies this?

As I see it, you don’t cross the eastbound roadway, as eastbound traffic can exit from either lane of the circular roadway. You enter either lane of the eastbound roadway. Well, I suppose that it depends on where you consider the eastbound roadway to end and the northbound one to begin. In terms of traffic flows, they overlap. And in a single-lane roundabout you can’t be positioned to the left of exiting traffic: you are in line with it.

Pingback: Some Dutch roundabouts | John S. Allen's Bicycle Blog