In his article “The Great Schism: Federal Bicycle Safety Regulation and the Unraveling of American Bicycle Planning” (library access info; subscription-based online access), historian Bruce Epperson claims, among other things, that cycling educator John Forester hardly made any advance over the earlier work of author Fred DeLong. I’d like to address that claim.

Forester, an immigrant to the USA from England, has acknowledged a debt to British cycling advocates; also to the work of the Motorcycle Safety Foundation in the USA — but Forester’s codifying the principles of road use for cyclists and supporting these principles on the basis of safety research was pioneering and game-changing.

I’ll give just one case in point here: advice on avoiding the hazard of opening doors of parked motor vehicles.

The following is from the 2nd edition (1975) of Forester’s Effective Cycling, page 3.1-5.

3.1.6 PARKED CARS

Don’t think only of the width of the parked car, but see every one as if it has its door open. Drivers of parked cars habitually open doors into the space in which you ride, because they know that cars don’t use that space. They also swing their front ends out to see if they can reenter traffic. You’ve all been cautioned to be prepared to stop. That’s baloney issued by non-cyclists. Why should they ask you to stop, just because you’re not strong enough to tear off their door? You can’t do it. At 15 mph it takes more than two car lengths to recognize a danger and stop, and you can’t see the danger two car lengths ahead. If you’re caught that way you have only one choice; dodge out into the traffic lane. It’s much safer to ride there consistently in the first place. So ride far enough away from a string of parked cars to clear an open door. If there are gaps in the string don’t dodge out of the traffic lane between the cars, because entering a traffic stream is one of the significant causes of car/bike collisions. Don’t make yourself enter the stream more often than necessary. Make only one exception: if there’s a solitary parked car ahead with big windows and low seat back, so you can positively see it’s empty, then ride close to it.

The tone is rather abrasive as is common with Forester, but the advice is way ahead of anything else available at the time. Elsewhere in the book, Forester supports this advice with a review of research data showing that rear-end collisions are rare — and rarer yet for cyclists who ride predictably.

Now, let’s look at advice on the dooring hazard from three bicycling books which were very popular in the 1970s — as far as I know, the three most popular in the USA.

First, the advice in the 1974 edition of Eugene Sloane’s The New Complete Book of Bicycling, pages 24 and 25.

- Never ride on a city street where parking is not allowed. There is simply no room for you between the traffic and the gutter on streets were car parking is forbidden. Such streets are high-traffic through streets. Cars might drive you right into the curb, or drive behind you honking madly because your bike is moving too slowly.

- As a corollary to the above, always ride on city streets where car parking is allowed and, in fact, where cars are parked. By laws, traffic is supposed to allow from thirty to thirty-six inches, up to a full three feet, on streets where cars are parked, to allow for the doors of parked cars to open easily. (Unfortunately, this is not always adhered to.) If you are a reasonably skilled cyclist and can ride straight, thirty inches will be all you will need. You’ll even have room to spare.

- Watch out for car doors opening ahead of you when riding on streets with parked cars! Discourteous drivers have whipped in ahead of me, parked their cars, and opened the door on the driver’s side, all in one motion, forcing me to veer out into the stream of traffic to avoid running into them. As you cycle on streets with parked cars, keep a close watch on the cars as far ahead as you can see. I have trained myself to watch parked cars for a block ahead, and to notice what’s going on in all the parked cars on that block.

- In particular, watch through the rear windows and look at the side view mirrors of parked cars. These will help you know if a driver or passenger is about to open a door. You may notice a driver who appears immobile and waiting, but I have found that this does not mean that he won’t suddenly leap out of his car. Some cities and states have an ordinance that makes the driver liable for any accidents caused by his opening a door on the traffic side, but you will still be better off if you can avoid running into a car door any time. Watch out especially for children in cars: they are always unpredictable.

The whiplash protector above car seats can hide the actions of a driver who may be about to open a door, since it covers much of his head area. So be doubly careful; assume that any car in which you can’t see the driver’s side may have an occupant who’s about to open his street-side door in front of you.

Some of this advice is truly bizarre. Gutter riding and door-zone riding are the only options Sloane presents. He considers the door zone to be a safety zone! His advice to look for signs that a car door is about to open is conventional and impractical. Just how it is possible to make practical use of a bicycle while only riding on streets with parking is a mystery to me.

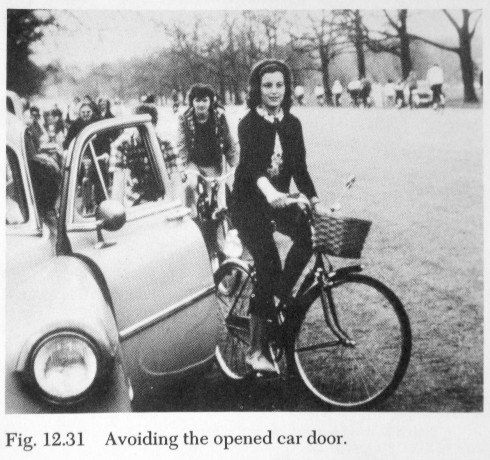

Now, here is the advice from the 1974 edition of DeLong’s Guide to Bicycles and Bicycling, the Art and Science, page 220, by A. Fred DeLong. DeLong repeated this in the 1978 edition, though Forester had already published his second edition of Effective Cycling. DeLong’s paragraphs about car-door avoidance are accompanied by a photo of cyclists practicing evasion of an opening door. As Forester pointed out, swerving risks a collision with an overtaking motor vehicle.

The Opened Car Door

It is against the law in most states for a driver to open his door on the street side in the face of oncoming traffic. The opening of a curbside door several feet from the curb — far enough from the curb to permit a cyclist to pass on the right — is less illegal. Yet both these actions happen often. When passing cars which have an occupant on your side, anticipate that he might open a door in your path. Note any action — the motion of a shoulder or arm — that could signify he is about to open the door. The cyclist may be able to avoid a door if swung open without warning through his rapid maneuvering skill if no high-speed traffic is approaching from the rear. But all too often, the door is opened so quickly that a painful crash occurs. Thus the cyclist, being the one who can sustain more damage, must learn how to prevent this type of accident before riding on traveled streets.

In a series of parked cars, station several occupants who will open the door without warning in the path of riders taking the test. The rider should approach slowly at first and than at increased speeds. The little indications of an obstacle-to-be become apparent. The evasive maneuver, practiced shortly before in our rapid turn on sight signal, is here put to the test!

And here is advice from the 1978 edition of Richard’s Bicycle Book, by Richard Ballantine, pages 123-124

Very often you will be riding next to parked cars. Be especially careful of motorists opening doors in your path. Exhaust smoke and faces in rear-view mirrors are tips. Even if a motorist looks right at you and is seemingly waiting for you to pass, give her/him a wide berth. Believe it or not, you may not register on his-her consciousness, and she/he may open the door in your face.

Ballantine — British — is the only one of these authors other than Forester to advise riding outside the door zone, but Ballantine doesn’t support this advice with safety research, and his advice isn’t consistent or detailed.

Game changing. Have I made my case?

And a couple of final notes:

- Forester has reviewed and critiqued Epperson’s article.

- Forehttp://johnforester.com/Articles/Social/Epperson%20Review%20TLJ.htmster has also been criticized by people who are concerned, among other things, that his advice on lane positioning isn’t strong enough. I’ll let that accusation stand, but its fair, I think, to cut him some slack. Let’s not forget that he was — the game changer.

Pingback: Acknowledging John Forester — the game changer | John S. Allen's Bicycle Blog

Interesting post. I hadn’t known about Harold Munn before.

Fascinating history. Thank you.

Pingback: John S. Allen's Bicycle Blog