My 10-year-old son Jacob’s school year hadn’t started yet on that brilliant, clear September morning. My wife had left for work. I had a business appointment in Belmont, a few miles from our home. Jacob and I set out for Belmont around 9 AM on our tandem bicycle. There wouldn’t be much traffic; the morning rush hour had passed. I had 30 years of safe cycling in Boston-area traffic, and little concern about our completing the trip safely.

Through an open car window I heard a word or two…Boeing 757 airliner…I got a spooky feeling. No radios were playing music or the boom chicka chicka booom chicka rant (expletive) rant rant rant which passes as music. I’d gladly have had that instead, thank you.

Jacob and I were turning left from where the white car is in the picture. Note the hedge on the far left corner.

Jacob and I were waiting just to the right of the double yellow line at a red light, to turn left from Waverley Street onto Thomas Street, near Belmont Center. Both streets are relatively narrow two-lane, two-way streets with light traffic. My left arm was extended in a very clear left turn signal. The traffic light turned green, and just as I began to swing the tandem to the left, I heard “beep beep” of a car horn behind us. A small gray sedan going about 30 mph passed us on the left side of the street, an insanely hazardous maneuver not only because of the possible collision with us, but also because someone might be making a right turn on red from Thomas Street, and would of course be looking the other way for traffic. A hedge blocked the view around the corner, too.

…I’ve just described two classic bicycle-on-wrong-side-of-the-street crash types, only with roles switched around…

Jacob and I rode the couple of hundred yards to the Belmont police station and spoke with Officer MacEachern, who was very supportive and professional. I didn’t get a look at the driver, but Jacob did, and identified her as a woman with brown or black hair (dyed?) and, he thought, wearing glasses. We reported the license number of the car, 350 JBA. The officer verified that it was for a gray Toyota Corolla sedan, and told us that it belonged to a 75 year old woman who lived in Belmont.

Officer MacEachern said that his department unfortunately could not issue a citation, since an officer had not seen the incident, but that he would go have a talk with the driver and that it might be possible to pull her license if she is incompetent.

I can understand being temporarily out of one’s mind. One time, I was injured but felt no pain, even ignored the grating of bone on bone, just had to get — home. Once a truck strayed into my lane and sideswiped my car. Only my quick swerve avoided a full head-on crash. I was going to turn around and chase after the truck, except that my wife calmed me down.

Maybe the driver was the daughter of the car’s owner, who was in turmoil…maybe she had children at home and hoped to spend her final minutes with them.

Maybe she had someone on one of those planes — two flew from Boston — or in one of those buildings.

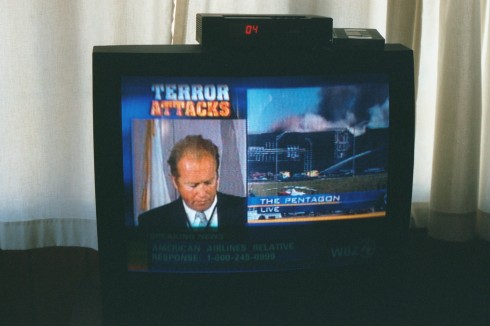

Jacob and I rode on to the home of my client where I shot the photo below.

And that is how my son and I might have been killed on September 11 2001, not by Al Queda fanatics in red-hot hatred, though very likely through a ripple effect of their apocalyptic, ruinous madness onto someone I would probably have been happy to have as my next-door neighbor.

I went back a few weeks later and took the picture of the intersection, so I could include it in what is mercifully the story of a non-event and gets news coverage only here. Even if Jacob and I had been killed or gone to the hospital, our crash would have gotten even less attention than bicycle crashes usually do, on that day.

A take-away? Every variety of opinion about Al Qaeda has probably already been expressed so I’ll only say this: adrenalin is a powerful mind-altering drug. It is available only by prescription except when you make it yourself, and because you do, police can’t cite you for it after a crash. But still, please think twice…