Should the pavement in a crosswalk, or special on-street bicycle facility, be painted a special color? Under what conditions? What color?

European countries use color. Let’s look at a few examples and see what they might teach us.

First let me say that my showing treatments here does not mean I endorse them. In the first couple of examples below, running a bike lane around the outside of a roundabout defeats the purpose of the roundabout in maintaining smooth traffic flow. Having cyclists and motorists merge into a single, slow flow of traffic has been shown safer for the cyclists too.

That said, this pink bike lane is in Thisted, Denmark — photo taken in 2006.

Roundabout with pink bike lane, Thisted, Denmark. Photo by Gordon Renkes.

This sea-blue bike lane in another roundabout is in Lyngby, Denmark.

Roundabout, Lyngby, Denmark, with blue-painted bike lane. Photo by Ryan Snyder from 2011 Association of Bicycle and Pedestrian Professionals calendar.

These bright blue-green lanes are in Copenhagen, Denmark.

Blue-green bike lanes in Copenhagen. Photo by Jon Kaplan

This red bike lane is in Winterthur, Switzerland.

Bike lane in conflict zone, Winterthur, Switzerland. Photo by James Mackay

As these photos show, there is no consistent color for carpet painting of bike lanes in Europe. German-speaking countries do appear to have settled on red, but Denmark has used at least three different colors in recent years.

There are issues with the effectiveness of color too. A couple of years ago, the US Federal Government sponsored a scan tour so traffic engineers and planners from around the country could examine bicycle and pedestrian facilities in Europe. According to one participant in the scan tour, Denmark uses paint only on one or two bicycle routes through an intersection, having found that using it on more routes negates any benefit. Clearly, it is important to address such issues.

What message does the color convey? A common use is to indicate conflict zones — where motorists must expect bicyclists and yield to them. At other times, color is used where no such conflict exists. Here is an example from Bristol, in England where the message is probably “no cars here”:

Barrier-separated bikeway with colored pavement, Bristol, England. Photo by James Mackay

Also according to the scan-tour participant, Switzerland uses red only where there is a history of crashes — leading to inconsistency in the message because crashes happen for different reasons. In the following example, colored pavement indicates a place of refuge from motor traffic — quite the opposite of the conflict zone in the previous Swiss example.

Who is the message of colored pavement supposed to be for? Bicyclists? Motorists? Both? Here it is apparently only for bicyclists.

Swiss use of colored pavement in non-conflict zone. Photo by Nicklaus Schranz.

Now let’s look at some US examples. The first common bike-lane color in the USA was blue, as used in Portland, Oregon. This bike lane in Cambridge, Massachusetts followed Portland’s example:

Cambridge, Massachusetts blue lane

Blue led to objections, because it already had a designated use in the US vocabulary of colors: handicapped parking spaces.

Green was proposed instead, and it is on the way to become a standard. Unlike blue, it shows up under the monochromatic yellow-orange of sodium-vapor streetlamps as well as the blue-green of mercury-vapor lamps. Green markings are the subject of several experiments testing their use under various conditions.

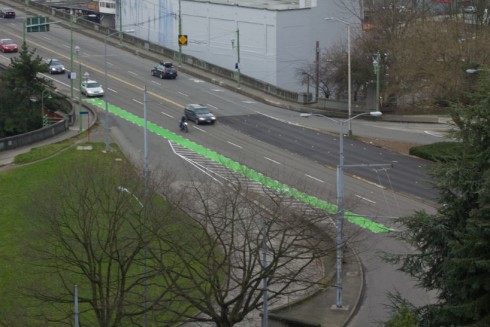

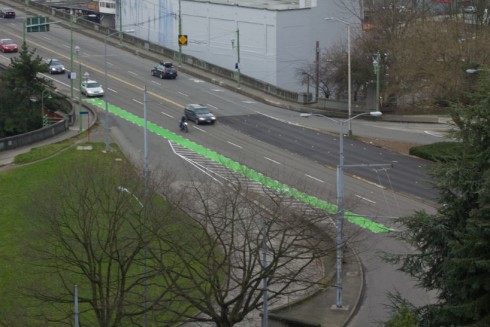

Green bike lane in Seattle, Washington

Yes, experiments. To be included in the national reference, the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices, and to be approved for general use, a new treatment has to be tested to see whether it affects behavior in an intended and desirable way. This is reasonable in the light of safety issues and expense. Where does it make sense to use paint; what consistent and understandable message might the paint send? What about durability of the paint; should it be reflectorized…there’s a tradeoff: reflectorized paint is slipperier. And so on.

Any state, city or town may install a nonstandard treatment and is exempted from legal liability if it works with the Federal Government and the National Committee on Uniform Traffic Control Devices, collects data and prepares a report on how the treatment worked.

Some communities don’t bother. Madison, Wisconsin has installed this crimson bike box. Crimson, even more than the European red, looks nearly black under both types of streetlights.

Crimson bike box in Madison, Wisconsin. Craig Schreiner/Wisconsin State Journal photo.

Madison, Wisconsin, of all places — a city with a long-standing and most knowledgeable bicycle program staff — one of the best in the nation. A city which has in the past known how to be innovative in ways that really work — see this example — and how to avoid costly and deadly mistakes.

Why the crimson bike box, then?

For many American bicycling advocates, trips to Europe take on the aura of a religious pilgrimage. Anything in Europe has to be better than what we do here, even if it isn’t.

As an aside: this reminds me of the American inferiority complex about European painting and music around the year 1900. American composers and artists who imitated European styles are largely forgotten today. We remember the American originals, who, certainly, adopted much from European styles, but who found their own voice. Scott Joplin. Charles Ives. George Gershwin. Duke Ellington. Aaron Copland. Bessie Smith, Billie Holliday, Ella Fitzgerald, Andy Warhol, Georgia O’Keeffe… but I digress.

It’s more than a question of an inferiority complex. It’s also about corporate lobbying. Bikes Belong, the bicycle industry’s political lobby, organizes its own scan tours. The goal of this lobby is to increase sales of bicycles — and why bother with troublesome, boring, nerdy details. Instead of sending professional program staff, Bikes Belong sends politicians. This is from the Bikes Belong Web site:

Zach [Vanderkooy] leads our project to make U.S. bicycling safer and more appealing by helping cities adapt the world’s best bike facility designs, policies, and programs inspired by leading bicycling cities in Europe.

And this is from a story on the Madison.com news blog:

The bike boxes are the first project from a European fact-finding tour of bicycle-friendly cities in Germany and the Netherlands that Madison Mayor Dave Cieslewicz, Dane County Executive Kathleen Falk and 19 other civic and business [leaders] made last month.

If you work for the bicycle program staff of a city, the Mayor is your boss, and you do what the Mayor tells you to do, or you can very well lose your job.

I wrote that before I learned of the following:

Arthur Ross, Madison’s long-time, nationally-recognized bicycle and pedestrian program manager, is being demoted — see this story. Whether it has to do directly with the crimson bike box or not, I don’t know yet.

I’ve said it before: in planning for bicycling, we need to do better than the Europeans. Certainly so on the issue of painted pavement, because, clearly, Europe doesn’t use it in any consistent or logical way. We need to do better with other, similar issues too, and because we face bigger and different challenges — and because it would be very unfortunate to lose the opportunity to do better.

In its turn, Europe may learn from us too.