© 1979, Mary S. Allen

| My earliest memory of my Aunt Lulu is an Impressionistic blur of her sitting at the Chickering grand piano my grandparents had bought her, playing a Strauss waltz with dove hands, her dainty shoes pumping away at the brass pedals. On the wall in that same capacious living room hung a gilt-framed oil portrait of three children, Aunt Lulu, my mother, and my Uncle Ira. The artist had placed Lulu in the middle, for her bisque doll face, blue eyes, and golden curls outshone any attributes of her more somber siblings. |

Lulu (center) and the author's mother Helen in their

late teens or early twenties, ca. 1905, and

unidentified boy, at a dock on Lake Ontario

.jpg)

| The woman at the piano, then about thirty, had maintained her exquisite coloring. But

she had been too well-fed by my grandparents and had become topheavily overweight; her

slim, shapely legs, modishly visible to the knee in that flapper era, looked inadequate

for her ample torso. "A barrel on toothpicks", my father described her. To clothe this problem flesh, Aunt Lulu shopped for the most expensive, well-cut suits and dresses B. Forman or Projansky of Rochester could proffer (alterations extra). On that day of the memory she wore a powder blue wool that made her eyes even bluer. Following the waltz she fingered out a light opera excerpt, singing the words in a sweet soprano. |

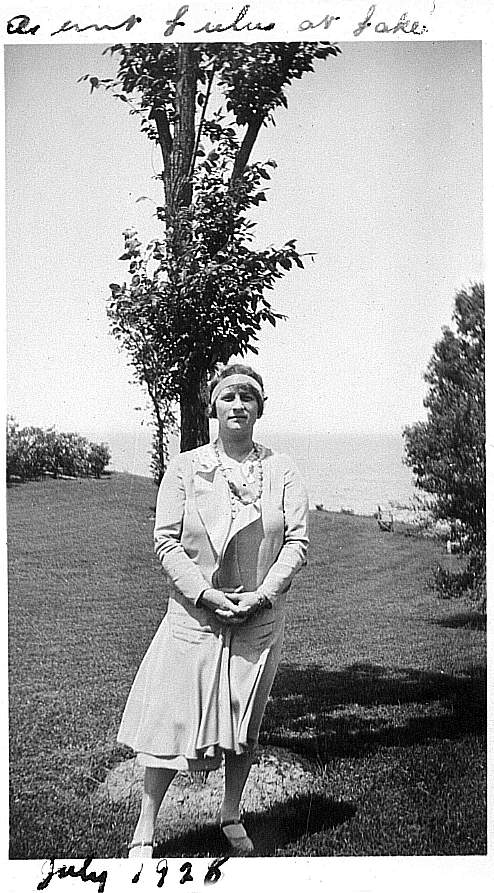

The "barrel on toothpicks":

Lulu at her parents' house on Lake Ontario, July 1928.

Handwritten caption by the author's sister,

Helen W. Stewart Jr.

| I could always tell when my Aunt Lulu was visiting at my parents' house, for from the one-room school I attended just up the road I could see her Packard gleaming parked by our mailbox. Although Aunt Lulu seemed inept -- she had dropped out of Vassar, never cooked, never even attempted a volunteer job, she drove constantly and well, which few ladies did in those days, preferring to employ chauffeurs. |

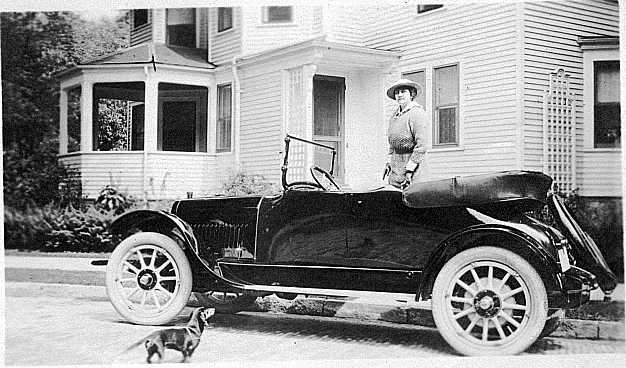

Lulu and the gleaming Packard, in front of the home

where she lived with her parents, 1 Upton Park, Rochester.

| When I came in from school she would he sipping tea with my mother, nibbling on one of

Mother's lush gingerbreads, offering suggestions as to how Mother should bring her

daughters up and criticisms of Father's rustic life (my parents, both city-bred, had moved

onto a farm). Aunt Lulu could not endure the unsavory garb my sister and I changed to when we were around the house - awful khaki shorts and shirts from a camping-goods store. She did talk Mother into having our straggling hair shingle-bobbed to be in style, and once she got me to a shampoo at her hairdresser`s, from which I emerged in tears, as the shampoo basin's marble rim had width suitable for a giraffe's neck, but not a child's. But to balance this, Aunt Lulu took us to the circus every spring, to relieve my mother, she said. When we visited my grandparents, Aunt Lulu supervised our table manners: "Take your hand off the table when you eat:" "Don't palm your bread!" "Helen (my mother) how can you let them stuff their mouths so? "Elbows off!" My mother and we, all conspiring, complied with her orders while with her, and then lapsed into our usual informal habits when at home. She couldn't, though, persuade my sister and me to curtsy. Aunt Lulu's dulcet voice and piercing opinions on everything from Paderewski to politics gathered her a group of friends who enjoyed congregating at my grandfather's house. She especially liked musical people, and the notables of the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra often graced my grandma's copiously laden table. My father, who snarled at Aunt Lulu periodically, labeled them a bunch of dilettantes. This was not quite true, as her coterie included at least three conductors. (Instrumentalists were less welcome). When my sister and I were teenagers she persuaded my grandfather to buy us series tickets to the Rochester Philharmonic matinee concerts. Although we began the series with giggling at the outrageous hats ladies of fashion wore to concerts, the magic of the great masters of music seeped into our consciousnesses, to stay forever. When I was fourteen Aunt Lulu hopefully introduced me to André, the son of a displaced Russian countess friend, Nina, who was currently married to the Eastman School of Music Orchestra director. André had a Russian accent which devastated me, but my nose ran when we went ice skating, and any potential romance was thus dampened. About every two or three years Aunt Lulu went abroad. Steamer trunks would appear in my grandparents' halls; packages would be delivered from Forman's containing silk blouses, leather pocketbooks, satin gowns, hand-embroidered lingerie, tiny high-heeled slippers. These choice items would be packed to accompany Aunt Lulu on the Rotterdam or the City of Paris or another such magnificently named ocean liner to Rome or Paris or Hamburg. We would watch for postcards with exciting stamps and scenes upon them, and brief notes of her journeys' highlights. If my grandfather ever objected to these lavish trips, I never heard about it. My father, however, had much to say. Then for three successive years Aunt Lulu went only to Rome. And even I, shielded though I was from family truths, learned she might be engaged. She was supposed to have met a dashing Italian, a pianist whom she had heard playing beautifully while she was upstairs in an inn, to whom she had subsequently demanded an introduction. He was a marchese, and a composer (of one popular song, we later learned). "A count of no account," said my father. She brought Francesco back to Rochester after her wedding in Rome. He was ten years younger than she, a brooding, dark man who refused to play anything on the piano for us. My grandfather was incensed at the marriage, at Aunt Lulu's turning Catholic (as she had never believed in anything) and at her decision to settle in Rome. |

Lulu at a café, probably in Rome

.jpg)

| Air mail letters stamped with an emblem denoting she was a Marchesa would come to me throughout college and the early years of my marriage. She wrote of guests, of her husband, dear Fran, and of her loyal maid, whom she paid five dollars a month. Then suddenly she showed a new return address. While they had been away in the summer, their house in Rome had been demolished during World War Two activity. She related this as serenely as her accounts of trips to the Alps. |

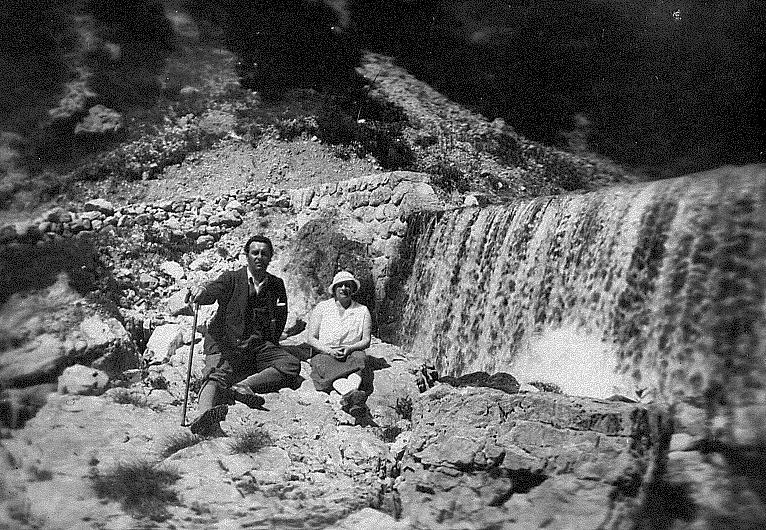

Lulu and Fran at a dam in Italy,

around 1930.

| The last time I saw Aunt Lulu she had come back to Rochester to visit and to maintain her American citizenship. In her sixties by then, and thinner, her face was still remarkable and her wit sparkling, She did not criticize me once but was enthralled by my having a one year old son, although she didn't dare touch him. She even approved of my husband. Before she left she bought me a pressure cooker as a gift- she who had never cooked! It was one of the most practical gifts I have ever received. |

Lulu and Fran in Italy, around 1950

.jpg)

| [Note by Mary S. Allen's son, John S. Allen: Aunt Lulu's survival in Fascist Italy during the Second World War is more remarkable in that her family of origin was Jewish. I suspect that she just didn't tell anyone.] |