The Chicago Bike Lane Design Guide, published by the Pedestrian and Bicycle Information Center of the University of North Carolina in cooperation with the Chicagoland Bicycle Federation and the City of Chicago, is available online on the NACTO site.

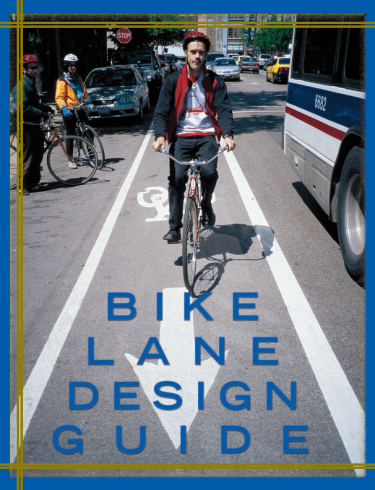

What would be a cyclist’s safest line of travel in the situation shown? Safest would be in line with the motor traffic, as counterintuitive as that may seem. Every credible bicycling education program advises this. That is where motorists have a good view of cyclists and interact with us according to the normal rules of the road. On the street shown, with only one lane for motor vehicles in the bicyclists’ direction of travel, riding in line with motor traffic would, certainly, be inconvenient for the motorists. So, perhaps a better solution would be to choose another street. Chicago is a grid city and offers many choices. Different street improvements might also be considered.

But, what does the cover show? Here it is.

There are some oddities about the photo — I’ll describe them first, before getting to my main point.

- The bicyclist’s helmet is too far back on his head, and so, not strapped on securely either.

- The saddle of his bicycle is too low, and he is pedaling on the arches of his feet, making pedaling inefficient and suggesting that he does not know the best technique for stopping and restarting.

- His trouser leg is not secured against catching in the chain.

- I’d prefer that cyclists wear cycling gloves and brighter-colored clothing, though I don’t indulge in finger-pointing against cyclists who don’t.

All in all, the cyclist looks awkward. It appears to me that the photo is intended to show that a newbie, awkward, timid bicyclist can find relief from anxiety by riding in a bike lane. Or maybe the people who did this photo shoot didn’t know any better — and that is troubling on the cover of a guide published by the organizations it identifies as its creators.

This is a posed photo shoot. If the cyclist had kept riding, he would have collided with the photographer. Even the bus probably was recruited, stopped so its picture could be taken. Choices in staging this photo, not only in selecting it, were intentional.

But here is the main point: though knowledgeable bicyclists had been warning about riding within range of an opening door of a parked car for decades, the bicyclist shown is riding in the middle of a bike lane adjacent to a parking lane, in the door zone. The bus shown passing the bicyclist carries the implication that the bike lane makes this interaction safe.

An opening car door throws a bicyclist out into the street. The same year the Guide was published, a cyclist in Cambridge, Massachusetts, a brilliant and accomplished graduate student, was doored and thrown against the side of a city bus. She fell under its rear wheels and was crushed to death. I wrote about that incident shortly thereafter. Many similar incidents have occurred over the years, and their number continues to increase.

I have posted comments on the Chicago Bike Lane Guide’s approach to the question of the door zone on another page.

And what good is the Chicago guide if the city will go farther in the wrong direction like so: https://chi.streetsblog.org/2017/08/24/dashed-bike-lanes-will-be-going-in-on-milwaukee-in-wicker-park-next-week/

https://chi.streetsblog.org/2017/08/30/eyes-on-the-street-a-first-look-at-new-dashed-bike-lanes-on-milwaukee-avenue/

Too, there’s the problem of riding to the right of a large vehicle. Drivers of those large vehicles can’t always see well to the right of their vehicles and can’t snuggle up to the right edge of the roadway (as legally required) to prepare for a right turn so a bicyclist riding there faces considerable risk.

Here in Minnesota very few bike vs. motor vehicle crashes involve large vehicles, but those large vehicle crashes are much more likely to kill the cyclist.

I’ll leave the technical side and focus on the semantics of the cover. I agree with JSA that it’s probably intended to communicate a “newbie” or occasional cyclist, but it does everything wrong. Its symbols are all negative. You NEVER communicate a class or group identity except with positive signs, and you always portray a little on the high side – after all, everyone thinks they are a little better than they are.

The best example recently is the cover of the newest edition of John Forester’s “Effective Cycling.” MIT put a professionally-shot photo, medium close, full cover, of a young woman, dressed business casual, upright bicycle, 3/4 front angle, clearly urban setting, clearly on the street, but background mostly fuzzed. She is calm, relaxed, in control. The message: “you might have heard that this is hard, macho stuff. Nah. Anyone can do it. So can you.” (Now, is that so? Maybe yes, maybe no. An issue for another day.) My point is: that cover communicates! Is that young woman “average”? No! But she communicates “average”! She is credible.

After thinking about JSA’s post for a week and looking at the Chicago cover and the MIT cover, it finally struck me: the Chicago cover is a satire of the new “Effective Cycling” cover. Gotta be. The geeky involuntary. The sneering club cyclists. Someone at UNC has a sense of humor. I wonder if Chicago was late paying their bill.

Actually the Chicago guide was published in 2002, so maybe the new Effective Cycling cover is an attempt to do better. As to what you identify as sneering club cyclists, I see them as advocates cheering the newbie on. Can you actually read the expressions on their faces? I can’t. The picture is too small. But rather than cheering the newbie on, or sneering, I’d hope that they were offering useful advice. “Here, let me adjust your helmet.” “This street might be a bit intimidating for you, how about using the street one block over which isn’t a bus route.” “Keep out of the door zone; you’ll feel less pressure to ride in it on that street.” “I’ll go ride with you and that will help you get comfortable with it.”

I just thought they were waiting for an opportunity to turn left and continue on their way …

2002? Now that’s interesting. That’s right about the time the Boub v. Township of Wayne case was working its way through the Illinois State court system, and local governments were ripping out bike lanes and signed trails right and left. Any “physical manifestation” that cyclists were an “intended” user of the roadway (including the sidewalk) waived absolute local government sovereign immunity. As far as I know, that’s still the law, but it has turned out that being subject to a normal duty of care (equal to that owed to motor vehicle users) wasn’t the liability threat everyone feared.

Please clarify: what was that liability threat and who was that everybody?

It was so complex that I wrote a 60,000 word article about it in the John Marshall Law Review. Many states have sovereign immunity, and throw that blanket of protection over some or all local subdivisions. Through a 40-year labyrinth of lazy court analysis and bad statutory drafting, Illinois ended up with a statute that said that local governments (not counties; municipalities and townships) had no duty of care and were absolutely immune from negligence on roadways unless the user was both intended and permitted.

It’s apparent that the legislative intent was to bypass the old English language of “invitee” and “licensee.” (It was meant to apply to lots more than just roads.) Kids playing sandlot baseball without objection on an empty city field are invitees; kids playing organized little league baseball in a baseball complex are licensees. The standards of reasonable due care are different.

On roads, the law ran into a fatal semantic brick wall. How can you not be a licensee on a public right-of-way, a local road? Anyway, the court “solved” the problem by determining that on roadways, motor vehicles were always “intended and permitted,” but that all other road users were not “intended,” and thus by statute were excluded from local government duty of care. However, if the local government “manifested physical evidence of intent” through signage, striping, or so on, then the designated user was covered by liability. This, of course, created a severe disincentive to provide such markings and many townships along a cross-national signed trail pulled out the signage. Undetermined at that time (2004) was whether the “physical manifestation of intent” opened a duty of care on the entire roadway, or merely that portion of the roadway referenced by the physical manifestation.

You almost have to read the paper to grasp the awesomeness of the bizarreness and aggregated institutional indifference behind the logic. It really did start out making sense and then metastasized into something unrecognizable.

Photographers (often instructed by art directors) are frequently blatantly wrong when trying to show “accurate” images. I once saw a beautiful hunting long bow, strung backwards, and the model had the sharply pointed wrong side of the handle digging into her hand. Strung backwards and pulled, the once expensive bow was rendered unsafe to ever use. (Spoiler: I had years of lessons from the Olympic Archery coach in the 70’s and I was even a National Archery Association Certified Instructor. The coach was one of the instructors). More concerned with lighting and composition, being “correct” in a photo is difficult. Blame the editors/authors for not insisting on a “correct” photo.

The bicycling activists who called for the photo shoot, and the editors, were so incompetent, or blindered,

as not to realize how foolish it looks — as with the archery photo you mention. Still, the issues are somewhat different in that the bicycling photo was intended to make a political point, as I described, in support of bike lanes. Here’s another example, more like yours, showing Middlebury College students out hunting. The consequences could be more dire than with your example. http://streetsmarts.bostonbiker.org/2016/01/05/whats-wrong-with-this-picture/