No, not reliable, though some are better than others. Some are also supposed to confer an aerodynamic advantage.

Some have a smooth surface which can deflect a cyclist. That is still no guarantee that the cyclist will escape serious injury or death. Other side guards are only open frameworks which can catch and drag a bicycle. A lot of what I have seen is little more than window dressing.

The side guard in the image below from a post on the Treehugger blog has no aerodynamic advantage and could easily guide a cyclist into the rear wheels of the truck.

A cyclist can easily go under the side guard shown in the image below, from a Portland, Oregon blog post. A cyclist who is leaning against the side guard is guided into the fender bracket and fender, and the front of the turning wheel, which can pull the cyclist down. There is another wheel behind the one in the photo.

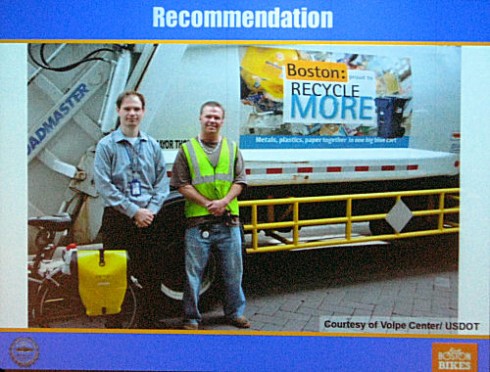

The side guard on a Boston garbage truck in the photo below — my own screen shot from the 2013 Boston Bikes annual update presentation — is only an open framework which could easily catch and drag a bicycle.

A truck which is turning right off-tracks to the right. A cyclist can be pushed onto his/her right side, and goes under, feet to the left, head to the right. Or, if an overtaking truck contacts the left handlebar end, or if the right handlebar end contacts a slower or stopped vehicle or other obstruction, the handlebar turns to the right and the cyclist slumps to the left, headfirst.

To be as effective as possible for either aerodynamics or injury prevention, side guards must cover the wheels. Though that is practical, none of the ones shown do.

But no practical side guard can go low enough reliably to prevent a cyclist from going underneath. The side guard would drag at raised railroad crossings, driveway aprons, speed tables etc. Even if the side guard did go low enough, it would sweep the fallen cyclist across the road surface, possibly to be crushed against a parked car or a curb.

Below are three photos I shot of my bicycle which sanitation workers in my home town of Waltham, Massachusetts, USA were kind enough to let me take. First a wide view. My bike was on the left side of the truck, as the workers were busy on the other side.

Next, the bicycle under the truck as it would be if pushed over and the truck was steering in its direction.

And finally, a bicycle guided along the side of the truck, with the handlebar sliding against the side guard. If the truck is going faster than the bicycle, this would steer the front wheel away from the truck and topple the cyclist into the truck’s rear wheels headfirst. The handlebar end could also be hooked by the vertical bar at the end of the side guard, dragging the bicycle while the rider is dumped onto the wheel.

Fatalities have occurred when cyclists went under buses, which have low side panels — but the wheels are uncovered. The Dana Laird fatality in Cambridge, Massachusetts is one of two in the Boston rea of which I know. The handlebar’s striking a stationary or slower object on the opposite side from the moving truck or bus will topple the rider into the truck or bus. Ms. Laird’s right handlebar end is reported to have struck the opening door of a parked vehicle, steering her front wheel to the right and toppling her to the left.

The bicycling advocacy community, as shown in the blog posts I’ve cited, mostly offers praise and promotion of sub-optimal versions of side guards, a measure which, even if executed as well as possible, offers only a weak, last-resort solution to the problem of truck underruns.

Most of the comments I see on the blogs I linked to consider it perfectly normal for motor traffic to turn right from the left side of cyclists, and to design infrastructure — bike lanes in particular — to formalize this conflict. The commenters also would like to give cyclists carte blanche to overtake close to the right side of large trucks, and place all the responsibility on truck drivers to avoid off-tracking over the cyclists. Side guards do not make defensive driving unnecessary either for bicyclists or for motorists.

Cyclists are vulnerable road users, but vulnerability is not the same as defenselessness. It is rarely heard from today’s crop of bicycling advocates, but a cyclist can prevent collisions with trucks and buses by not riding close to the side of them. There’s a wild contradiction in playing on the vulnerability, naiveté and defenselessness of novice cyclists to promote bicycle use with measures — particularly, bike lanes striped up to intersections — which lure cyclists into the death trap next to a truck ro bus. Regardless of whoever may be held legally at fault in underrun collisions, cyclists have the ability to prevent them, and preventing them is the first order of business.

Want to learn how to defend yourself against going under a truck? Detailed advice on avoiding bicycle/truck conflicts may be found on the CyclingSavvy Web site.

Additional comments about the political situation which promotes underrun collisions may be found on the CommuteOrlando site.

![Victoria Crescent, Newport [Wales], 1982](https://john-s-allen.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/image-2-for-sustrans-cymru-images-gallery-820590116.jpg)