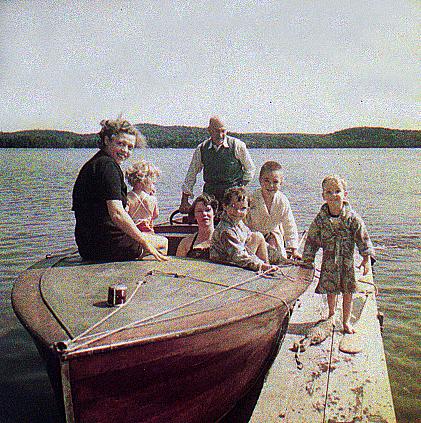

Gordon W. Allen photo |

John S. Allen

I remember having had a rather formal relationship with my Uncle Harold when I was a child vacationing in Dwight. I'm sure that I brought it on myself to some degree, because I was a socially inept, demanding, awkward, sometimes obnoxious child. Besides, I was not Harold's own grandchild. Harold understandably spent more time with members of his own branch of the family, who often were also vacationing in Dwight.

One summer, I had a longing, or obsession, as children sometimes have, to do something which I felt was essential to my personal development: to go for rides in Uncle Harold's motorboat. When I heard the motorboat out on the bay, I would stand on the dock in front of Uncle Harold's cottage, the Pine Cone, waiting for him to return so I could help moor the boat to the dock, in the hope that he would offer to take me for a ride. I got fewer rides than I hoped for. When my mother found out what I was doing, she gave me a short but pointed lecture about begging for favors.

One occasion on which I did get to ride in the motorboat,

photo dated 1953. Everyone else in the photo

is from Harold's branch of the family.

Left to right, Dot, Anne, Peggy, Harold, Susi, me, Bill.

Gordon W. Allen photo |

But there's another story which centers on the motorboat. Three Harolds -- Uncle Harold, his son Harold Jr. and Harold Welch -- were down on the Pine Cone dock one day attempting to reassemble the motorboat's engine. The cylinder head was off and the three Harolds couldn't figure out how to get it back on again. The head bolts would not thread into the bolt holes. And I, then aged 8 or 9, suggested that maybe these bolts should turn the opposite way. They did -- for some reason, they were threaded counterclockwise. All of the Harolds were impressed.

In The Stewarts of Dwight, Uncle Harold. includes a note about his 16 year old grandnephew's having shot, processed and printed a photograph of him and his brother. So, clearly, he felt familial pride about me too, whatever else he may have felt.

I think that he must have felt some tension about differences between his branch of the family and mine. My grandparents and parents did not steadily tread the path that had been traditional in the family. My grandfather, Harold's brother, had studied for the ministry but had failed to build a career as Harold and two of the other brothers had. While my grandfather had a great love of the outdoors and of summering in Dwight, he had never owned a cottage in the Dwight area, though four of the other five brothers each built and owned one. My grandfather's not having a cottage may have been due to my grandparents' rather tight financial status, or to my grandmother's holding the purse strings.

In identifying the different faces in photos of himself with his siblings, my grandfather always notes the high professional status achieved by all his brothers. I wonder how it must have felt to him to identify Harold, D.D., Dean of the School of Theology, and Norman, Ph.D. in Biology, and Arthur, M.S., Vice President, Gleason Gear Works, Fred, Professor of Theology, and Hugh, active minister for 40 years, but to identify himself as "The Rev. Alexander M. Stewart," knowing he had not had a church for thirty years and had failed to graduate from Harvard, where Harold had succeeded. Perhaps my grandfather's sense of mission in his historical work gave him enough pride not to compare himself unkindly with his brothers, but he was to some degree a Dostoyevskian character, the holy fool of the family.

My grandmother grew up in a Jewish family and did not attend either Jewish or Christian religious services as an adult, except as required by family obligations. The marriage of my grandmother and grandfather, viewed as an act of rebellion by many in their families, more or less closed the door to my grandfather's pursuit of a career in the ministry. My grandfather always said grace at the dinner table, but without mentioning Jesus Christ.

On the other side of my family, my father was raised a Baptist but became a freethinker and agnostic. Finding a common denominator for their various religious origins, my parents attended the Unitarian Church, a church without a creed, and I attended its Sunday School, which exposed young people to a study of good works, scientific method and comparative religion -- including, in the junior high school years, visits to services at other churches and a Jewish temple. My Sunday School textbook pointed out, in detail, the differences of belief and practice of the different denominations.

The Unitarian church fostered my observation that the many differing beliefs couldn't all be correct, and from this I advanced to the conclusion that the Unitarians must be best of all because we didn't fall for any of them. Only later did transactional psychology and the youth culture of the sixties give me the language and concepts to understand that whatever people might believe, the road to truth must start from where people are now, truth may be found in many different ways and take many different forms, and it is important to establish a working relationship with other people. I come to realize how my smug skepticism placed barriers between me and other people. Despite this reservation, I still regard the Unitarian Sunday School as one of the most valuable educational experiences of my youth: it taught me to think critically, something which the public schools persistently avoided doing.

Despite the Unitarianism, every Sunday while in Dwight, my branch of the family -- except for my grandmother and my father -- would attend the church services at which Harold officiated. My father and grandmother found a way to beg off. -- my father would often find it compelling to work on his watercolor paintings on Sunday mornings and my grandmother would "sit for" his paintings -- she said this with a laugh, because my father painted only landscapes, not portraits. So my father and grandmother drove off to some scenic location. My father would paint, and my grandmother would read a book.

My father provided a role model for my skepticism year round, not only in his avoiding the Dwight church services. As my mother was preparing dinner, my father would raise his before-dinner martini and proclaim to his wife and children: "I don't know whether there is a God," This was his creed and his communion. My father's tone of voice suggested that there was some comfort and certainty in this statement. Even when I was a child, his ritual felt a bit uncomfortable to me. Smugness over a martini did not feel right to me in confronting the deepest mysteries of existence, whatever a person might believe. Still, it was as a skeptical observer, rather than a seeker, that I attended the Dwight church services.

| Right, Uncle Harold in an informal moment. Below, the 12

year old skeptic misfit |

|

I found the services fascinating. Many observations from them have remained in my memory. Here's one. Before the children were let out for the Children's Activity, we would sing, with Harold's voice booming over all the others thanks to the PA system,

Jesus loves me, this I know,

For the Bible tells me so.

Little ones to Him belong;

They are weak, and He is strong.

Yes, Jesus loves me,

Yes, Jesus loves me,

Yes, Jesus loves me,

The Bible tells me so.

(As I go back to the church these days, the words have been changed and the children sing "with his love, we shall be strong." Apparently, as we move into a new millennium, the popularity of high self-esteem has trumped that of original sin. [Complete lyrics of both versions, with comments]. I prefer the solid, confident Protestant hymn lyrics, even if I do not believe what the words say. When I was a kid, only we Unitarians had thoroughly rewritten the hymns.The windy 19th century Unitarian "Truth and Beauty" hymn lyrics just didn't cut it as poetry, and neither does the new version of "Jesus Loves Me"!).

But I digress. Uncle Harold had a strong, booming voice. I suppose that he had trained his voice in his preparation for the ministry, when public address systems did not yet exist. When he told family anecdotes on the porch of his cottage, his hearty laugh would echo in the trees.

On those occasions, and most of the time, he spoke with a standard North American accent. Though his family was Canadian, he spent most of his youth and career in the United States, and he did not even have the typical Scottish-tinged Ontario pronunciation of "out" somewhere between "oot" and "oat". Yet a most remarkable change came over his voice at the Sunday services. In the formal parts of the service -- the prayers, the doxology -- his voice took on a very British high church accent and intonation. He didn't say "In the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, Amen" he said "INthenameofthe Faaaaatheh [pause] ANDofthe Sonnnnnnn [pause] andof the Heyley Spidit, Amen."

Baptist is a generally a denomination of people without pretensions. At the time, I ascribed this pronunciation to Harold's Anglophilia. Certainly, he was an Anglophile, as were many English-speaking Canadians. When he intoned his prayer at the Church services, he lent special emphasis to God's blessing the Queen. But I also imagined then, and then learned for a fact, that his mannered speech was common in the clergy. I have also heard it on broadcasts of the Service of Lessons and Carols from England, and in Cardinal Cushing's prayer at the funeral of President Kennedy.

In my skepticism, I considered that the Queen was already rather well blessed, and perhaps other people might have a greater need of good wishes and charitable attention. Harold also regularly asked God to bless the U.S. President, who was at the time General Eisenhower. Harold also requested that a rather long list of Canadian politicians be blessed. The list of those to be blessed descended in hierarchical order, circling closer and closer toward home. Harold asked that the United Church of Canada be blessed, and our Dwight church. Once, and I was there to hear it, he prayed for conversion of the Jews. When my Grandma got back from sitting for my father's paintings and heard about this from my mother, Grandma's annoyance was personal. She and Uncle Harold had known each other since they were high school classmates some 60 years earlier.

Harold was proud of his family and its accomplishments, and thankful for the privileges he enjoyed. His grandfather was a pioneer preacher, his father, dean of a school of theology. Harold and three of his brothers became ordained Baptist ministers, but Harold followed most closely in his father's footsteps. Harold's first church was in humble Coudersport, Pennsylvania, but he continued with larger churches at Corning, New York, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and Oak Park, Illinois. In Harold's final position before retirement, he served, at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, like his father, as Dean of a School of Theology, .

Sometimes I find Harold's pride a bit out of keeping with the lessons of the Scripture he espoused -- "as you do unto the least of these, my brethren..." Harold's grandfather, Alexander Stewart, never lived in the sturdy Scottish stone house illustrated in Harold's family history. Rather, a loose pile of stones marks the probable location of the humble hut where Alexander Stewart lived as a child. (Why would he have wanted to emigrate anyway if he had lived in comfort in Scotland?) And as Elizabeth H. Stewart's research revealed, the link Harold assumed between Alexander Stewart and a line of noble ancestors also was incorrect.

Harold's genealogical quests in The Stewarts of Dwight consist mostly of an attempt to link the family to British nobility, with nary a nod of the head toward the hundreds of humble, hardworking people (and certainly, also a more than a few rogues, scoundrels, and wretched unfortunates) among our ancestors. Though the names of most of our ancestors are lost to history, we might yet acknowledge them. In Harold's coverage of the most recent few generations, he does turn to an examination of the full spectrum of lines of descent, male and female, though notably, Harold does emphasize a number of high officials in the Canadian government, through his wife's family, and several additional possibilities for noble ancestors!

Success in the clergy requires a thorough knowledge of Scripture, and the ability to compose sermons, but also strong fundraising and diplomatic skills. Uncle Harold clearly was good at all of these things, but I think at some cost in his willingness at times to say what he meant, to see conflicts and contradictions clearly or.to follow his thoughts to where they might derail his career. In such a career there is tension between keeping the boat upright, on one hand, and steering toward enlightenment, on the other.

In The Stewarts of Dwight, he bends himself a bit out of shape to avoid saying anything unpleasant about family members, including the redoubtable Mother Ruth. He does gently chide Ruth a couple of times for taking advantage of opportunities, and by implication, taking advantage of family members. Part of his clemency toward her might just reflect his having had his own cottage in which to spend the summers, rather than staying as a guest in Alderside under her regime. "Regime," by the way, is Uncle Harold's word. My mother has written a description of Grandma Ruth and of that "regime" from the point of view of a guest in Alderside, which see.

Harold treats most Dwight residents like the common people in Shakespeare's historical dramas, as comic relief. Though he expresses real respect for some of them and deference to most of them, the issue of class differences can not be denied. How would you feel if you were a relative of Herbert O'Toole, with Harold putting his words into Mr. O'Toole's mouth, and in dialect?

My mother has told me that once, on the verandah of the Pine Cone, Harold had said that if he had his career to do over again, he would probably choose to be a Unitarian. He said this when he had retired. I don't know how strongly Harold meant that he would have been a Unitarian. He might have said it to be kind to my mother, and to my grandmother.

Harold had three sons. Like him, all were successful, though none took up the ministry as a career. Paul, the eldest, rose to Vice President at the Maytag Corporation and was highly active in civic affairs. Gordon worked in the OSS during the Second World War, and then in the CIA, where he rose to Inspector General -- I learned this by reading an article in, of all places, Rolling Stone magazine in the late 1970's that mentioned a trip he made to Laos. According to the article, the purpose of the trip was to follow up allegations that the US had condoned a drug trade which financed tribes which took the American side in the ongoing conflict in Southeast Asia. When Gordon finally began describing his career at all to the family, he described this trip as more of a pre-retirement junket -- he told a story about how he had received an ornate, handmade rifle as a gift from the tribespeople.

And there was Harold Jr., who spent much of his career working on atomic bomb tests. I learned the harrowing details of one of these in an article in an old Saturday Evening Post which had been kept by the previous, packrat inhabitants of the house where my sister's hippie commune in Oregon lived . Though Harold Jr. was a kindly and friendly man, I never felt completely comfortable around him, having lived in terror of nuclear annihilation for most of my life.

All in all, Harold's Sr.'s legacy is complicated. But there is one part of it with which I am completely in accord: he preserved our family history. For this, we can be enduringly thankful to him.