Table of Contents

Previous: Alderside Summers

Next: The Cottages

III. DWIGHT LOREGreaves Robson | Sayings

recounted by Norman | William Thompson Here are set down many of the incidents and tales we recall, mostly from the early days, but some from more recent summers. There is no special order to this portion of the story, but in general what is more recent comes after what belongs to earlier years, and sometimes stories are grouped around one person, either the teller of the tale, or the central figure in it. Greaves RobsonNo name is more highly regarded by the Stewart men than that of Greaves Robson, whose father, William G. Robson, was the pioneer settler at Birkendale on Ten Mile Bay. Greaves was a hero to us - a loyal friend, our guide on our first camping trips, a man of boundless back-woods experience, who possessed a vein of humor that made his tales as humorous as they were interesting. For years he rivalled Fred Marsh as the best captain and pilot on the Lake of Bays. Finally he fell in love and married and moved out of our sphere to live in Barrie. His son, John Robson, entered the Presbyterian ministry, and after a fine pastorate at Huntsville moved to a large church in Toronto. John has sometimes been the preacher at our summer services in the Stewart Memorial Church, and he still comes back for summer vacations to the point furthest out on the west side of Ten Mile Bay, where his father had a cottage. Here is one of Greaves's tales: One evening the Nishka, I believe it was, was making its trip from South Portage to its many points of call. Its passengers were mostly women from the country-side who had been in Huntsville shopping. Alex Ford, who was a very tall young Englishman, was acting as engineer. Suddenly the boat ran on a sand-bar and tipped to one side. The women were terribly scared and began holding a prayer-meeting in the bow, seeking deliverance. Alex guessed what had happened and he let his long body over the side of the boat near the engine-room till his feet hit the sand. Then he worked his way along the side towards.the bow seeking an advantageous position from which to heave the boat off. As he came towards the bow he spied the women on their knees, and exclaimed, "Ladies, if you would take your prayer meeting down to the stern of the boat, I could push her off a lot easier!" And here, another, slightly less credible: A young and inexperienced Englishman took up land back of Dorset, probably on Otter Lake. He bought some stock for the place and went into Dorset to take the animals out. He was very puzzled as to how he was going to get a cow, a calf, a cat and a dog all out to his place together. Happening to meet Jennie Robson, he consulted her. She made the following clever suggestion: "That's easy. Get a rope to lead the cow. Tie the calf to the cow's tail. Put your goods on the cow's back, and get two bags, one for the cat and one for she dog. Put them in, and tie them together and throw them over the calf's back. Then you lead the cow." Apparently the young man took her seriously, for somewhere on the road someone met him. In one hand he had the rope leading the cow, and in the other he had the cows tail, and he was leading the calf. When asked what had happened, he explained that he had done just as Jennie Robson had told him, but the cat and the dog got fighting and scared the calf which had jumped and pulled out the cows tail. "And what are you going to do with the tail?" "Oh", said the young Englishman, "I'm going to take it home and sew it on. She'll need it when the flies get bad." Sayings remembered by NormanNorman reported the following, which he called 'Some Quaint Sayings We Remember" Alfred Ketch: "They's two kinds of Ivory. They's an Ivory that's pison, and they's an ivory that ain't pison, and the Ivory that's pison is Pison Ivory." ditto (trying out our field glasses for the first time) "Gosh, that there loon looks awful nears. But she ain't no nearer than she is!" "And look at my shoes - gosh, if they were that big it would take a whole cowhide to make one shoe." ditto "Once our bull fetched up with a porcupine. He got his snout full of them quills. We got him in the barn and got his head between the posts, and we laid a log on his neck. George, he stood on the log, and father pulled them out with pinchers. Gosh, ye could'a heard him ball to Dorset. Winnie Keown: "I don't go to Dr. Hart. He's kill or cure." "Mostly cure, I suppose?" "Naw, KILL." Steve Thompson: (When Norman bought Innisfree) "No, Norman, that line ain't quite right. I know, 'cause Basset, you know, the government, and Ford Ketch, and Wack Thompson (not young Wack from the Portage, but old Wack from up in Sinkler [i.e. Sinclair -- JSA]) we run the first line here years ago. Now stand here. She goes down your acre here and crosses that water there, and jumps clean over the side of that island, crosses the bay again and jumps right into that sny, and up Willard's creek and into the mash. In there Ketch thought he heard a wild beast of some sort, and he let out a yell and run off towards Murray's. That scared the government - Basset -and he dropped his peek-sticks and his chain and took off fer Huntsville like a jack-rabbit. I kin see him runnin yet. Well, anyway, it goes through that mash and up the oats and slam - right into the middle of Willard's barn. Now, Norman, that's the line! George Keown: (Discussing why Norman had to wait to get his deed to Innisfree) "well, it's got to go through what they call Suggary Cour (Surrogate Court) It's a process of law. But I can't understand, if there was any swearing to be done, why didn't Irwin (the lawyer) have me swear fernint him when he was in?" Mr. Emberson - at Sunday dinner after father had become a professor at Rochester Theological Seminary - "A-A---A---Yass - I read in the Baptist that you had gone into the Cemetery." Sign at the Dwight Orangeman's Celebration "Band Concert at 7:30. Dancing all night - God Save the King." John F.: (Met on the road to Marsh's Falls) "Good morning, John, been fishing?" "Ya, I'm going to stock my lake." "Wonderful'. What have you caught, in your can?" "'Taint much, but it's a beginning. I got two minnies, one catty --- and a crawfish!" ditto: "Did you make that wagon you planned to make?" "Yes, I've got slices of logs fer wheels. Works pretty good. But one busted. Ye can see I've got the grindstone on today." Eli Leach: one day we had to move the ice-house: It was a difficult job, and at one juncture Eli Leach was under the ice-house seeing what move should come next. He called out-- "Eeve away a bit. Give ter an 'alf a hinch or a little mucher." Ralph Gouldie, on the outside, "That's right, give Mr. Leach a little mucher." Note that a lumberman left on a blaze on a tree when he was walking to Oxtongue Lake from Dwight, where he couldn't wait for his pal: "You'll find me a Hell Peace up this road." Norman adds, "I didn't know there was much peace in Hell!" William ThompsonIn the early years William Tbompson used to supply us with lamb, and, incidentally, the overall price at the beginning was nine or ten cents a pound. He killed and prepared the lamb at his farm, and then put it into his skiff and rowed it the three miles to Alderside. When he rounded the big point he got a line on the back of his boat and a couple of trees, and rowed perfectly straight on a bee line to our beach. Once on that line, he never looked around on the mile and a quarter stretch till he came to the shore. One hot day we boys built a raft for diving, and we drove a stake into the bottom of the lake and tied the raft to it. That evening Mr. Thompson delivered our lamb. As usual he never:turned his head while rowing in, and just by chance our raft was precisely in his line. He was a very strong rower, and the inevitable crash almost threw him out of the boat. I do not know whether he was more surprised or indignant. How we boys felt is a matter for the imagination, but however else we felt, manifestly we got a great kick out of the situation. Maybe Mr. Thompson would say, as Greaves Robson did when he took off his hat to shelter a match while lighting his pipe and a bee lit on his bald spot and stung him, "I's sprised!" Mrs. Bob KeownMrs. Bob Keown's size was a matter of amazement among the younger boys of our crowd. One day some of us, including little 'D.A.' Clarke (later member of the Board of Control of Hamilton) were approaching the creek bridge in a boat just as Mrs. Keown rather waddled down from Dwight on her way home. 'D.A.' gazed at her in intense curiosity, and then exclaimed: "Why, she isn't so big - but she's bigger in her lowers than she is in her uppers!" LonelinessBefore there were so many people around, so many cars passing, radio and television, and mail every day, conversation was more highly prized than now. Even Dickey Wilson, who was exceedingly shy, passing on the road, said, "Good-day", and about fifteen feet further along, paused and turned and said, "Good-by". Bob Keown, the last of his father's family to come from Ireland, was very friendly and full of talk. One day he came down the hill, and seeing father sitting on the Alderside verandah, he leaned against the fence for a chat: "There be them that says stones grow", said Bob. "Yes", father replied with a lift in his voice. "They's nothing to it. When I come into this country, in Huntsville there was one big stone house right on the corner. I've been watchin' it ever since, and it ain't growed a bit." Once old Tom from Cooper's Lake came down, and looking for conversation and finding no one on the verandah, he wandered around to the kitchen window, where he got his elbow comfortably resting on the window-sill, and adjusting his pipe began talking to our cook of that season: "Now where did you come from?" queried Tom. "I came from the county of Gray," said the cook. "Ye did!" exclaimed Tom, "Why that's where my old woman come from." "Yes? and what was her name before you married her?" That was the $65,000 question for Tom. He adjusted his pipe, moved his hat into a convenient position for scratching his head, and scratched and thought. "Well now", he said, "I clean done forgot what her name was." One day I went to Coopers Lake and wanted to borrow a boat, so I went to Tom Keown's house. Mrs. Keown was there, and, of course, it was all right for me to have the boat. I was leaving, and had got several rods from the house when Mrs. Keown appeared in the door, hungry for conversation. "How's your ma?" she called. "Fine". I called back. "And how's your pa?" "He's well, too". I said. There was a pause. What more was there to talk about? Mrs. Keown planted her fists on her ample hips and thought. At she had it! "Say, is your old grandpa living yet?" "Yes." "Well, now, ain't that a great joke! Ha, ha, ha." The circumstances of the pioneer days made people want to hear others talk. Greaves Robson lived alone on the shore of a back lake northeast of Dorset for a considerable time. Three months passed without his seeing anyone else. When finally old British Bateman came paddling down the lake in the evening light, Greaves did not dare move for fear the canoe would disappear, and when old Bateman landed, he made him come into the cabin and sit up all night talking. The Tom Paris family was snowed in for a month one winter when they were living in the Blackwell house on Devil's Angle Lake, and no one came by. Another human voice must have had a welcome sound after that. George KeownGeorge Keown - Tom's son from Cooper's Lake - was a handsome man, tall, broad, well-balanced, with a regular, good-looking face. He was a magnificent axe-man and woodsman, and he could manage a camp of lumber-jacks very well, but his schooling had been somewhat neglected, as it was far from his home to the school, and his father was not greatly interested in his sons' education. George was a personal friend of mine, and one whom I prized. One day we met on the road and had the following conversation: George: "You know, Harold, it's funny about me and the old man." Harold: "What's funny about it, George?" George: "About me and the old man being the same age." Harold: "The same age - why, what do you mean?" George: "Yes, about us being the same age. I never could understand it till I was past twenty-one. You see, me and the old man was born on the same day, and I could never figure it out about us being the same age till just a little while ago." William KeownFor a great many years Willie Keown, Tom's son, went by the name of "Winnie", because that was the way he pronounced his name when he was small. He substituted 'n' for 'l'. In later years he overcame that, and one day when Isabel saluted him as "Winnie", he drew himself up with great dignity and said, "Mrs. Stewart, my name's William. So be it, but long, long ago, we are told, the first Mrs. Gouldie used sometimes to get Winnie to tell little stories by giving him some candy. The most noted one went like this: "Oncet they was two fennows, and they was walkin' up the road when they come on a honnow nog. One of them fennows crawned in one end of the nog, and when he got in, anong come an ond bear and he crawned in the other end of that honnow nog. Then the fennow on the inside says to the fennow on the outside, "What's darkenin' up that there hone?" And the fennow on the outside says to the fennow on the inside, "If I lets go of this here tain you'll see what's darkenin' up that there hone!" There was a picture on the wall of the living-room at Alderside near: the door. It was called 'The Love Letter'. In it a beautiful young woman was pictured holding a love letter to her lips, and on the table in front of her was a vase of flowers, evidently a gift from her lover. Willie came in one day, and was interested by the picture. He studied it quite a while, and then gave us this interpretation of it: "That old woman is a chewin' her old pipe, and there's her tobaccy." Many years passed from the time when Willie told about the 'honnow nog', and we were old friends now. One night in the early summer I met him in front of G. D. Atkinson's. The mosquitoes were biting furiously, but I thought I could pause long enough to pass the time of day without being eaten up by them. "How are you, William?" I said. "Well, I'm all right now, but I was awful sick in the winter." "Were you?" "Yes", said he, "You see, I went to one doctor and he couldn't find out what was the matter. Then I went to another, an' he couldn't, either. Then I went to another, an' he found out just what was wrong, an, he told me, an' he was right. I sez to him, I sez, I wisht you'd tell me what is the matter with me. An' he sez, Do yez want to know what is the matter with you?, An' I sez, Yes. An' he told me, an' he was right, fer he knew. An' I sez to him, Tell, tell me what is the matter. An' he sez, If yez wants to know, I'll tell you, an' he was right, fer he knew. A I sez, Well, tell me, an' he sez, Do you want to know what's the matter with you? An' I sez, Yes. An' he sez, I'll tell you what's the matter with you, an' he was right, an' he ups and sez, What's the matter with you is that you's a complete wreck." J.W.A. raising moneyAbout the turn of the century, John D. Rockefeller made an offer to double any funds the Rochester Theological Seminary might raise up to an amount of $150,000. President A. H. Strong of the Seminary persuaded the First Baptist Church of Rochester to release father from the pulpit for several months to raise the Seminary's share. Father went at his task, and in the end, I think, the entire fund was completed. When I went to Dwight that summer father had already $96,000 in cash and pledges. One evening I paddled along the shore towards the bluff, and, as I came to George Keown's place, he happened to be down on the shore and we had a little chat. "Well, what's your dad doin' now?" said George. I explained what father was doing, raising funds to meet Rockefeller's offer. "And how, much has your dad got now?" queried George. "Ninety-six thousand dollars". "Byes, oh! byes!" exclaimed George, "That man Rockeyfeller will be the sorry man they ever got your dad on the job when it comes time for payin' up." Sermon-tastersThere are sermon-tasters even in the back country, as witness this from Elsie Gouldie, who was probably not much more than ten at the time. "After your dad goes home, Charlie Schafer preaches." "How does he do?" I asked. "I'd rather hear my own dog preach than him!" And young Joe Smith, from Portage Bay, having heard both father and grandfather, remarked, "Oh, Joe Stewart's all right, but give me the old man." Eliza StoutOne summer we had Eliza Stout, whom mother brought from Rochester, as cook. Eliza was Irish herself, and as we travelled from Huntsville by boat through the lakes, she exclaimed to mother, My land! What a lot of water!" But there must be different kinds of Irish, for she had difficulty always understanding old Daddy Keown, who regularly rowed our milk supply over from the farm in the mornings. One day he brought some vegetables in a basket, which he forgot when he was leaving, and returned to get. Eliza was in the kitchen, and she related the incident as follows; "He come back and he sez, 'Me buskit!. And I sez, 'What did you bust?t And he sez, 'Me buskit'. And I sez, 'Land's sake what did you bust? I thought he'd bust some hinternal horgan of hiss'n." Fence climbingFred reminds us that at one time Mrs. Chas. Cunningham made desperate efforts to reduce and lose some of the pounds which their excellent fare at the Cunningham home seemed always destined to add to her. She even used to go down on the dock in the evening and skip rope in her efforts. Naturally getting around the country was a far different proposition for her from what it was for mother, who weighed sometimes a hundred pounds and sometimes ninety. Old Mrs. Keown summed the matter up thus: "Sure, Mrs. Sport Cunnigum, she's a loidy. When she's out walkin' and comes to a bar fence, she waits till they take the bars down and let her by. But Mrs. Stewart, she's no loidy at all, at all. When she comes to a bar fence, she climbs right over!" ApplesWhen we were small, Arthur and I went one day up to the Meredith farm - later Burns' and now Hill's farm - where we had been promised some apples. We got a big bag of them, and it was so full that it was difficult to get the top gathered together and tied. But apples were apples in those days at Dwight, and we had no intention of leaving any of them behind. It was quite a struggle for us to carry the bag. We took turns carrying it on our shoulders, in this way relieving each other, but every now and then the tie-string would come loose, and the apples would spill out on the ground. We'd gather them up and tie the bag again, only to have the accident repeat itself. Somewhere near Pete Newton's farm we met Bob Keown. I know we each hoped that he, being a man, would offer to carry the bag, but all he offered was advice as he saw us again trying to get the apples into the bag and get it tied. "I tell yez, byes, what yez should have done. Yez should have got one lang bag, and put part of the apples in each end, and put each end on every side of your neck." Old Mr. PrattOld Mr. Pratt was one of the early settlers at Dwight. Some came to settle for one reason and some for another, but old Mr. Pratt came because he had a vision in his mind. With two hundred acres in his possession he could visualize a beautiful garden and a manor house for himself such as his rich neighbors in the old country had owned. He picked his spot at Stony Point, with the river coming down one side, and the land gently rising back from the lake. He laid out straight walks and round flower plots and worked the ground along the walks into terraces, with perennials carefully arranged to set off the design of the garden. Finally he built a 'small ouse' where he lived while he attempted to make brick from the local clay for the 'great ouse' that was to be. From this there would be the most glorious outlook on the entire bay. Most of his vision never emerged from the state of being a dream. In England Mr. Pratt had been a watch-maker, and a sort of local exhorter of the Methodist Church. Sometimes at a union service in the village he was invited to sit on the platform with father and the student minister and pronounce the benediction. In my recollection these benedictions ascended with the sweep of a cathedral tower. They started somewhere on the level of the congregation and went up by assured and regular stages till they ended with an "Amen and Amen" somewhere among the angels, and the old man dropped into his seat red-faced, profusely perspiring, and almost exhausted. Charlie Pratt, the old man's son, came from England to join him. And a cow, with the astonishing name of 'Laura' was added to the family. It must have been lonesome for Charlie. One day I mentioned that to Mr. Pratt. "Oh, yes", he replied, "Sometimes Charlie does get lonesome, but when Charlie gets lonesome, 'e goes down by the shore and talks to Laura, and Laura drops a sympathizing tear." Finally, William, Charlie's brother, an a sister or two, came to make the family complete. William and Charlie went into building cottages. They built the two large ones now owned by Harry Hatch. But they had a falling-out and William left Dwight. One day I asked Charlie where William was, and he replied, "I don't know, and I don't care, and I hope I won't meet him, either in this life or in the life to come." I left him, feeling that I had had the final and complete answer. Cer--cho--oof!One evening I attended church. Isabel didn't. When I came home she asked about the service. I didn't tell her all about the sermon, but I told her the prologue at least. The minister rose to preach and said, "Friends, before I come to my text, I think I ought to tell you something else. Cer--cho--oof!" After recovering from his sneeze he continued, "Well, you see, last week we had a retreat for ministers, and I attended. We had some great speakers, but the greatest was Dr. Jackson, maker of Roman Meal - fastest selling cereal in Canada. Now a few years ago Dr. Jackson was so weak they thought he would die, but today he's past eighty, and he's stronger than most men of his age. He told us - Cer -- cho--oof! -pardon me - just how he got into such good condition. You see, every day he eats Roman Meal - fastest selling cereal in Canada - and he does not wear an undershirt, and every day he takes a plunge in the lake before breakfast. Cer -- choo--oof! Well, I've been trying to do as he says he does, and I'm not wearing any undershirt and I'm jumping in the lake every morning. Cer--choo--oof! I guess I've got a little cold to start with, but I think it will work out all right.„ Isabel was incredulous. But Dora Atkinson happened to have been at the service, and later she confirmed my report. John F. WilsonHow long John F. Wilson has been lead I do not know exactly, but his grave lay just across the road from Barnaby Lodge before Barnaby was built in 1922. One day father gave John F. an overcoat, and I remember the event for John stood in our old lean-to kitchen at Alderside scratching match after match with long strokes across the lids of the stove trying to light his pipe. It was hard to light the pipe because he used so many substitutes for tobacco, such as fern leaves, that did mot burn well. Well, he stood there scratching matches and saying, "This coat's a beauty. It's just like one the old man (grandfather) give me once, only it had a watch chain to hang it up by." That was before 1906, and John had been a familiar figure long before that. Once when Arthur Hamilton came up from Rochester, he gave John F. a stove-pipe hat as a joke. John wore it to church, walking down through the bush from Wilson's Lake. After church he held it proudly in his hand and said to me, "Better hat than it is a man, but the hat improves the man." John F. had an ingenious mind. When his log house on his lake seemed cold in winter he decided to warm it up by putting a layer of shingles on the outside. He had no shingles, and doubtless no money to buy shingles, so he overcame this difficulty by shingling the house with tin. Every time he saw a tin can he brought it home, pounded it flat, and nailed it on for a shingle. Cans of all kinds and all sizes were used, from five gallon tins to little fruit cans. I saw the house only a few years ago while on a walk with Phil Atkinson. He never got it entirely shingled, but at least two sides were finished, and they looked as amazing as Joseph's coat of many colors. John dressed with old trousers pulled up over his skinny frame, and a flannel or cotton shirt with a vest over it, usually unbottoned. He lacked a white collar, and a neck-tie, and a tie-pin, such as he saw others wearing, but this did not stump him. He fashioned himself a collar from a piece of black rubber out of an old discarded rain coat, then he got a piece of string for a neck-tie, and taking d piece of lead - probably tea lead melted into a small lump - he bored two little holes in it, and ran the ends of the string through the holes, and lo: he had necktie, collar, and tie-pin, marvellous to behold! But let John describe one of his own clever achievements. "Was you up my way, Harold?" "Yes", I replied. "Did you see my field of 'tatties?" "Yes." "Well, when I put those 'tatties in, the wee calves and the wee sheep used to run over them, so I thought I'd put up one of them bob wire fences and keep them off. So I just run one wire clean round the field, and the wee cows jump over it and the wee sheep crawl under it!" Another day he said, "A while ago I had some chickens hatch out, and them chickens had two sets of wings, one right back of the other, just where they ought to be." Here he began to stoop down, holding his walking-stick parallel to the ground until it was within three inches of the earth, talking as he did so. "And when them chickens got to be so high, a frost come up and killed them. Gosh, I wish them chickens had a' lived. I thought I was going to have a circus." Isabel took the children and went to the Presbyterian Church one Sunday afternoon. A student from Knox College was in charge of the service. Someone had placed a basket of ferns on the Communion table. After service had commenced, there was a rattling thumping noise at the front steps, and John F. came in and walked down the aisle to the front seat. He had a heavy chain around his waist with a long free end which was fastened to a walking stick to keep him from losing it. This had been the cause of the clatter at the door. John slumped into his seat with a further rattling of the cane and chain, but soon he was attracted by the ferns on the Communion Table, and wanting to see if they would make good pipe tobacco, he got up and shuffled over to them and picked a frond and rubbed it vigorously between his finger and thumb and sniffed it loudly. Then, being satisfied, he returned to his seat. The young man from Knox was having difficulties by this time holding the attention of his congregation. The afternoon was hot, and soon, like Bottom, John F. had 'an exposition of sleep' come upon him. He took two little limp-covered hymn books and laid them on the iron arm at the end of the pew, then he stretched out full length and laid his head on the books, and covered it with a disreputable red bandana handkerchief, and quickly went to sleep and snored like a man. Against all this competition the student minister bravely struggled to the end of the service, and Isabel, I know, out of a deep compassion, spoke a few well-chosen and consoling words to him at the door as she made her way with the children from the church. John was an exceedingly hungry man most of the time. They say he had to put an egg in his cheek to bring it out far enough to shave. One autumn Dicky, his son, worked for the Robsons on Ten Mile Bay, and at Christmas, Mary Robson gave him a good turkey and the makings of a large plum pudding as an extra reward to take home for the family dinner. She told me she gave him enough to last the Wilsons for a week. After Christmas, when he returned, she asked him how the dinner went. "Oh, fine", said Dick, "you see we put it all in the oven to cook at once, and the pudding was done first, so we ate all it, and then the turkey was done, so we ate all it, too." This constant hunger may throw light on John's behaviour at Communion. The bread was passed in slices from which the communicant was expected to break off a crumb. John took the whole slice, and when the cup was passed, he drained it. After church I heard him mumbling to himself, "Good! I wish they'd have it every Sunday." In John's perpetual starved state, I think this was an expression of genuine thankfulness, and no sacrilege was intended. I thought that Dicky was John's only child till one lay I met him and he said, "How many boys have you?" "Three", I answered."Well, I've got you beat. I've got five." "You have?" said, "Why, I thought Dick was your only child." "Nay", answered John proudly, "I've got four down in Orillia!" Sad as that, may seem to us, I am sure that these poor children were more comfortable in the Orillia institution than they would have been living at home with John and his wife. One morning early, grandfather was passing John's house just in time to see John going from his night's sleep in the chicken house to his own dwelling. The explanation was that it was more comfortable out there than indoors! John traded all his hay crop for a three-legged horse. "Oh, you old devil. why did you trade your hay for a three-legged horse?" asked grandfather. "Well", said John, "she can kick anyhow!" |

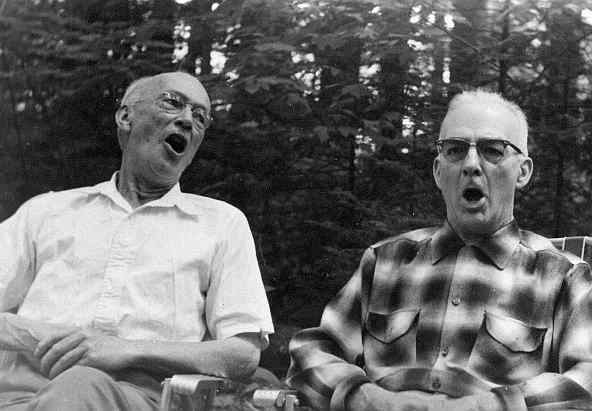

JOHN F. WILSON Always known to us as 'John F'. This snap was given to me by Mrs. Florence Boothby. Who took it, I do not know. The cigar is unusual. John F. always smoked a pipe, but someone gave him this cigar to get him to stand for a picture. Imagine him with a walking stick fastened to him by a chain that was secured around his waist, or with a high silk hat, which he wore one day to church! |

Peter Newton's Tales.It must have been around the turn of the century, and there were a number of us Stewart boys and one or two of our friends at Alderside in advance of mother and the rest of the family. We were fending for ourselves, and one evening we had a 'banquet'. In my recollection the chief dishes were speckled trout and wild strawberries. When we were at the table in the midst of our feast, in came Peter Newton to tell us that we were required either to provide two days of road-work, or to pay two dollars. We gladly took the road-work, and while none of us was equal to the kind of days work that any settler would do, Peter, as 'pad-master' for that year was willing to accept our services. While we were discussing this he got seated at the table, and as was natural, we asked him if he had seen any bears recently. "Wall, just one or two. But there was one last fall used to come into my corn field. There was a lang dead tree that lay from the woods into the field, and he used to come in on that tree trunk right into the field and stand there and eat corn. Wall, Sunday afternoon my wife's pa and ma came drivin' up in the buggy to visit. So I told the missus' pa about the bear. An' he sez, 'I know it's Sunday, Pete, but I'd awful like to get a shot at that bear.' So I sez, 'All right', an' he got in the buggy and started home to get his gun." (Home was four miles away, so it was some time before he returned). "I put the misses an' her ma an' the kids in the house, an' I crawled up on the peak of the barn to watch fer the bear. After quite a while, sure enough, out he come on the log into the field an' stood there a eatin' corn. I could see down the road, too, an' pretty soon I seen my woman's pa comin' up in the buggy. So I got down as quiet as I could, an' took his horse by the bridle to hold it, an' showed him where the bear was. He seen it, an' he went quiet like down into the field. I watched, an' he raised his gun an' fired, and he missed the bear. So the bear just stood there, an' the misses' pa stood there, too, with his gun in his hand. An' I waited fer him to shoot again, an' he just stood there, an' the bear he turned around slow like an' walked back on the log into the woods an' went away. An' when the missus' pa come up out of the field, I sez to him, 'Why didn't you take another shot? There wuz the bear sittin' waitin'?' An' he sez, sorta slow, 'Tell you the truth, Pete, I wus afraid of scarin' the bear'." "Now this ain't a bear story, but did I ever tell you about my Uncle George an' old Jimmy Cunnigum huntin' a deer? I ain't? Wall, maybe you recollect that wee bit of a lake back of my wife's pa's field. It wus in there. They went in last fall one day, an' took a canoe, the two of them an' a wee dog. So old Jimmy, he set up in the back of the canoe an' paddled, an' Uncle George he set up in the bow with the gun, an' the wee dog he run around the lake an' pretty soon he put a deer into the water just beside a long tree that had fallen into the lake. So the deer come swimmin' out on one side of the tree, an' Uncle George, he up an' fired, an' missed. The deer he struck fer land beside the tree, but the wee dog wus on that side of the tree an' drove him back, so he went around and tried the other side# an' the wee dog wus there. Uncle George he took another shot, an' when he missed, he just waited fer the deer to come round the tree an' he up an hit at him with all his might with the gun, an' the gun snapped out of his hand an' sank. The wee dog he kept runnin' from side to side of the tree on the shore puttin' the deer back each time he come around. Uncle George shouted to old Jimmy, 'Let me have a try with the paddle.' So old Jimmy he paddled fer all he wus worth towards the deer and handed the paddle to my Uncle George, an' he give the deer an awful whack an' bust the paddle, but he didn't hurt the deer. Well, the wee dog puts the deer back around the tree again, an' Uncle George he whips out his knife to try to cut its gambs, an' then he leaned over the bow of the canoe an' paddled with all his might with his hands. Old Jimmy Cunnigum set up straight in the back of the canoe, an' he sez, 'By George, George, yous'll make it yet!' My Uncle George he come up on the deer an' caught him by the tail an' pulled him up out of the water an' wus swingin' his knife to cut his gambs when the deer let out an awful kick at the side of the canoe an' most upset it. With that he swum to shore any made off into the woods." "But, boys, youse should hear my Uncle George tell that story.'' Bill Hood Moves to South PortageNorman recalled the story about Bill Hood's move to South Portage. I have an idea that Bill became so unpopular at Dwight that tire idea of a new location was attractive to him. However that may be, the time came to make the move, and Bill got a lumber scow and loaded all his goods on it and set off. Included in his possessions were a cow and a dog. Somewhere down in the narrows the dog scared the cow and the cow either jumped or fell overboard and swam for shore. So Bill, short one cow, put this notice up in the post-office: If anyone finds my cow, Amy BurnsAmy Burns became almost part of our family. She came to help us a few summers after we built the Pine Cone, and was with us for twenty summers or more, and one winter in Oak Park, Illinois. Even after she married George Chambers she would come to us for a week-end if we had any special guests for Sunday dinner, as when Dr. and Mrs. George Pidgeon and Dr. and Mrs. Otto Neimeier were with us, the Sunday Dr. Pidgeon preached in the little church. There was never anyone like Amy, and we were heart-broken when she died, and we always think of her when we pass the little Anglican cemetery at Grassmere on the way to Huntsville, and sometimes we stop the car and go and stand by her grave. Amy was born when the Burns family lived on their farm at Burns Lake a little way off the road between Miller Hill and the Quinn settlement on Long Lake. The family was much alone there. One winter Tom Burns was working at a mill at Portage and Mrs. Burns and the children were by themselves at the farm. Mrs. Burns was expecting a new arrival in the family. She had an arrangement with a friend at Miller Hill to come when she needed her. At last the time was near. A neighbor man - I think from the Quinn settlement - was passing, and he dropped in to see how she was and whether he could help her in any way, but she modestly sent him on his way. Then she called one of her children and told him to go as far as the gate by the road and to stand there until a certain boy came by on his way from school, and to bring the boy to the house. When her little tot brought the boy, she said to him, "You run back to Miller Hill and get Mrs. So-and-so, and tell her I want her now. And don't walk - run every step of the way!" Off the boy ran, out to the road, up hill and down dale, till he got to the woman's house and delivered his message. When the woman reached the Burns farm Mrs. Burns, all alone in the house, had given birth to twin babies. We first knew Amy when she was a girl in her 'teens clerking in Jimmy Asbury's store at Dwight. Weekends she would walk home alone, from Dwight to Coopers Lake, around the shore past Tom Keown's old deserted farm, back into the woods, up the steep, lonely path to Little Mountain Lake, around the end of the lake and up the bluff on the far side, past the point from which one could see Mountain Lake, Cooper's Lake, and the Lake of Bays at one sweep{A}, down through the woods by Big Mountain Lake and on through the great hardwood forest to Burns Lake, and so home. Eventually the family moved out from their farm and bought the Meredith place, near Cain's Corners, with its attractive big stone house which Robert Meridith had built for the girl he never married. It was then that Mrs. George Keown suggested that we get Amy to help us. Mrs. Burns, who had been in service with prominent families in the city before her marriage brought Amy down to us, and when she had inspected Amy's room and the conditions of her living with us, she agreed to let Amy work for us, and left her at the Pine Cone. Amy was young, attractive to look at, with beautiful eyes, possessed of much natural refinement, well brought up, quick witted, and always ready with an apt reply to anything said to her. She became a very fine housekeeper and cook. When we would arrive in the summer, the cottage would be cleaned, all the bedrooms made up, supper on the table, and Amy waiting to welcome us. She took great and increasing interest in the boys, always directing them to their chores and insisting on their doing them. She followed their interests constantly - specially their interest in girls - expressing her judgment and giving her counsel freely. The boys were very fond of her. As the years went on Amy came more and more to take charge of the household affairs, making the lists of things to be got in Huntsville, and even insisting on where they were to be bought. -- "Oh, no, Mrs, Stewart, put that back. It won't do for you to get your roast here at the A. and P. For these guests you must get it at Armstrong's." Amy never got over being a child of the bush. With all her refinement and interests - and she was in charge of Lieutenant Governor Albert Matthews's domestic arrangements for a number of years - the wild country was her delight. She saw the beauty in it, and thought everyone else should do the same. When she went to Oak Park with us for a year, she missed the woods amid the crowded houses. One day we went for a drive and turned down into the Forest Preserve. Amy almost jumped out of the car with a joyful cry, "Oh, the bush!" Her quick wit delighted all of us - father specially. One day she went off to pick wild strawberries and came home with a fine lot of rather large ones. Isabel said, "Where did you get these beautiful berries, Amy?" "Over ' in the cemetery", said Amy. "A rather queer place to go gathering berries, wasn't it?" said Isabel. "Maybe", answered Amy, "but then they have more body to them there." It would be an unpardonable omission to write about Dwight and not to write about Amy as a part of the story. A truly lovable and remarkable person, never to be forgotten! The AsburysFor many years Jimmy Asbury had a general merchandise store at Dwight. It was near the shore of the bay, and just west of Pine Grove Inn. The store was flourishing more than forty years ago when we built The Pine Cone, and most of our local trading was done there at that time. Jim married Annie Newton, and Annie's father, Pete, was a little regretful because he felt that Jim was robbing the cradle, as Annie was still in her 'teens. but the marriage was a good one and happy. Jim was a clever merchant, and long before the Magnagrip came on the market he was dragging nails out of the barrel with a large magnet, to save his fingers. By and by old Mr. Asbury died, and later Jim sold the place and moved to Oxtongue Lake, where he set up a store and cabins for motorists. Two of his sons were Vic and Art. One of tile boys - I think it was Vic - attained a certain fame during the Second World War. He was with the Canadian troops in England when one day the Queen came to visit the camp. For part of the time of her visit the soldiers were at ease, having refreshments of one kind and another. Vic saw the Queen near him, and stepped up to her holding out a bottle and saying, "Have a Coke, Queen". Art attained fame in a different way. After World War II, Bill Hatch, Col. Harry Hatch's son - who spent his summers with the other members of the family at Dwight on the old Pratt place - interested Art in motor boat racing, and they two used to race at regattas in ten horse-power motor boats. Art's interest continued and grew, and on the first Friday in November 1957, he drove Miss Supertest II, owned by Jim G. Thompson of London, Ontario, to a new world record of 184.449 miles per hour over a course on the Bay of Quinte near Trenton. This was six miles per hour faster than the record for propeller driven boats set up by Slo-Mo-Shun IV, set at Seattle, Washington, five years earlier. The engine of Miss Supertest II was a 2,000 horse power Rolls Royce Griffin. The Ross Autograph AlbumWhen Fred came to sell his cottage, the buyer was Air Commodore A. D. Ross. We were fortunate to secure such pleasant neighbors, and soon we all became friends. The "D" in Mr. Ross's initials stands for "Dwight" and it is no mere coincidence that a Dwight came to Dwight, for he is a grandson of H.P. Dwight, for whom the place was named. His paternal grandfather was a member of the first Canadian Parliament after Confederation. One day Marguerite Ross (Mrs. A.D.) showed us an autograph album which Dwight's grandmother Ross possessed, and for which the present generation has secured some names. She loaned me the album which contains an astonishing collection of autographs. So unusual are they that I am listing some of them here so that on our part they may not be forgotten. Arthur (Duke of Connaught) 1890, and again, 1896. Sir John A. MacDonald, and all the members of the first Cabinet. P. T. Barnum, Nov. 23, 1889. With his name he wrote, "The noblest art is that of making others happy." G. Garcia. He inscribed his name on the same page as Barnum's, and wrote, "And next to it is to fill ones pocket." 28/11/89. Albert Visetti. He drew a bar of music, and wrote, "Viva-Valse written for Madam Patti". Aberdeen - October 20, 1890. Henry Drummond Charles W. Gordon (Ralph Connor) Melba (Nellie) - October 12, 1912. Mrs. Humphrey Ward (Signed with her given name) Some members of the British Scientific Society, when its meeting was held in Toronto: Oliver Lodge John Milne Simon Newcomb A. R. Forsyth J. J. Thompson George - 1901 and Victoria Mary Edward P. - 22-10-19 (1919) Wilfred T. Grenfell Rudyard Kipling Henry Irving W. J. Bryan - May 4, 1909 -Lincoln, Nebraska. John Henry Jowett - Aug. 11/17. Tweedsmuir (John Buchan) Alexander of Tunis Elizabeth - Nov. 8th, 1951 Philip. The last two names were cleverly acquired. Commander and Mrs. Ross entertained Elizabeth's equerry at the time of the Royal Visit to Halifax. Marguerite showed the album to the equerry and remarked that the autographs of the royal couple would perfectly complete the list. He agreed, but said it was against the rules for Her Royal Highness to sign an autograph album except in a home where she was entertained. He suggested, however, that he might take the album and get the signatures on shipboard on the return journey and then send the album back. So he took the album. That evening there was a dinner for the Queen and Duke, and at it Marguerite noticed the equerry making some kind of joyous signals to her which she did not understand. As soon as dinner was over he came up to her and said, "The signatures are in the book. The Queen was delighted to do it." "Long live our gracious Queen", say I. Burial at NightEverything in the environment of Dwight is friendly, and this carries for the sweet little burying ground behind the church. I met Ann on the road one day and she hailed me saying, "Grandpa, Carol and I are going hunting for graves up behind the church." So, even for a child of five, the place held no terrors and no awesome atmosphere. Under our picnic table a man is buried. His friends strayed too far east in digging his grave in the days before there was a fence to mark boundaries. Mother Ruth chose to sit and read in Barnaby Lane facing the cemetery, and said that she liked the thought that crazy old Mrs. Burns and John F. - friends in the days of their earthly life - lay sleeping just across the road. Once Isabel and the boys saw a ghost over there at night, apparently digging, or working around a grave. There was no trace of him, or of his digging, in the morning. How often we have attended funeral services there, participating in them a good many times. And our own family circle extends to the quiet lot where mother, Mother Ruth, and father rest, and where Josephine and George lie close at hand. One Saturday evening in September, some years ago, Isabel and I were returning from paying some last bills at Lumina, and as we swung up Barnaby Lane, we saw lanterns in the grave yard and a number of men busy digging a grave. This was rather unusual, and so, after putting the car away, I went over to see what was happening. It appeared that Mrs. Bradley had died at North Bay, and was to be buried here. (I think she was a relative of Butt Woodcock's, and her husband was one of the Dwight Bradley family. They had lived for a time on the old Dabold place back of Pine Grove Inn). The undertaker in North Bay had sent word that the burial should not be postponed, and as his words were being taken literally, the burial was to be as soon as possible after the arrival of the midnight train in Huntsville bringing the casket from North Bay. The men around the grave reckoned that the undertaker from Huntsville would reach Dwight about 2:30 A.M., and they were hurrying to be ready. They asked me to take the service, which I said I would do. Two men were in the grave digging, and one man stood at each end above holding a lantern down into the excavation to illuminate the process. Several others, including Johnny Robertson and George Keown and little Hughie Corbett stood around watching and giving advice. Willie Tom was one of the diggers in the grave. Willie would go to one end and stamp his foot and call, "She's high here", and then to the other end, and with another stamp of his foot say, "She's low here". With this kind of guidance the digging went steadily on. After a while there arose a dispute as to how deep a grave should be. There was quite a lot of talk and finally it was decided that six feet was the proper depth. No one had a rule, but that was no problem, for Johnny Robertson could cut a gad in the bush exactly three feet long. He slipped off into the dark to cut one. Meanwhile the steady tramp, tramp went on in the grave, and Willie's voice kept announcing, "She's low there: she's high here". The diggers were throwing out their shovels of earth, and the adult watchers were offering their advice, when suddenly there was a slight sound from the bush where Johnnie had gone to cut his gad. "What's that?" cried Hughie Corbett in a startled voice. A head came up out of the grave, and with it a voice: "If you'se afraid of ghosts, kid, you'se had better be making for home." And from lower down the laconic, "She's high here". Johnnie returned with his yard-stick and the digging went steadily on. Suddenly one of the shovels slipped easily through some gravel on the side of the grave. "By George". cried George Keown, "you'se have run plumb into the end of that other grave down there. I tell ye once they had me movin' a baby's grave down in the lower part there, and my shovel run right into another grave, an' by George, that's the last time I'll ever do a thing like that, so it is." Finally, by all the measures that could be made, the grave was properly dug, and the diggers and onlookers slipped away into the night to prepare themselves for the burial service. I went home, set the alarm, got my New Testament, as I had no service book with me, and was prepared to dress and run over at the proper moment. Before the alarm sounded I was awakened by a very bright light in the bedroom. It was the head-light of the hearse as it rounded the corner from the road to go up to the cemetery. I jumped from bed and pulled on my clothes. Isabel leaned over from the side of the bed so that she could look from the window. She could see dark figures with flash-lights going up the slope to the grave. When I arrived I counted seventeen dark objects, which were the mourners, standing about, waiting for the service. It had not occurred to me that one cannot read lessons or prayers when there is no light. So there I was, dependent on memory. I made up my service as I went along, repeating all the suitable Scripture that I knew by heart. The casket was lowered, the benediction pronounced, and in the dark there was the thudding sound of earth falling on the casket to fill the grave. Then into the night, as mysteriously as they had come, the mourners slipped away. And so ended the only burial at night that I was ever called on to attend. August Morn One summer father and Mother Ruth secured a woman as housekeeper and cook. She was capable and good help, but somewhat eccentric. For one thing, she used to wait on table smoking a cigarette. She went for her swim early in the morning when no one was around, dressed in the fashion of the figure in the famous picture, September Morn. That summer the Atkinsons were entertaining an artist as one of their guests. He was doing a number of landscapes, and was taken with the view across the water from behind father's boathouse. So he got up early one morning to get it in the soft light of dawn. When he was well established behind his easel he looked up, and here was the eccentric housekeeper from Alderside descending for her morning dip. To be sure, she had a dressing-gown around her, but he thought it only fair to let her know he was close at hand, so he called out gently, "Oodle oodle". "Oodle, oodle", she answered, "You mind your business, and I'll mind mine!" How to Destroy a Wasp's Nest After church one Sunday morning last summer (1958), Harold Welch was standing on the road listening to a great deal of talk from Willie Keown - erstwhile Winnie - and finally Harold said, "I hear you are the best man around here at getting rid of wasps' nests, William. Tell me how you do it." "Well, I'll tell yez", said William, stretching out his hand with his thumb drawn back as far as possible from his fingers, "Yez goes up to it quiet, and yez shoves your fingers in over the top like that, an' yez shoves your thumb into the door, an' yez goes like that", giving his arm a broad.swing by which the nest would be thrown as far as possible, "any then yez stays away from it!" Try it some day - it works for William! Steamboat Days The charm of steamboats is gone from the Lake of Lays, but who that knew it will ever forget the boats on their regular trips coming down the bay, or the search-lights at night shining above the hills that separate Dwight Bay from the main channel, or the welcomes and farewells on the docks, or those blissful all-day picnics on the boats that took us from bay to bay and from point to point, and from dock to dock, all the way to Baysville, or Dorset, and back? Captain Hawkins had a boat on which some of the earliest settlers came to Dwight, but that is beyond our memory. I doubt if any of the family ever saw it. The first boat on the Lake of Bays we recall was Captain Marsh's Mary Louise. Then came Captain Denton's Florence. Then followed the Maple Leaf, the Equal Rights, the Iroquois, the Joe, the Nishka, the Mohawk Belle, the Bigwin boats, and a number of private steam launches. Besides all these, there were for a time the alligators operated by lumber companies. These looked like scows with heavy engines and side-wheels, and were used for towing rafts of logs. Greaves Robson and Fred Marsh were the two outstanding captains in steamboat history on our lake. Later captains never visited so many small private docks, or towed logs from so many deep inlets as did these two, and they got to know every nook and turn in the variegated shoreline perfectly. Fred Marsh, old Captain Marsh's son, was not moderate in his drinking, and frequently he was well under the influence. Once when we were late coming in from Huntsville we arrived at South Portage to find the Mary L. with its fires out, its steam low, and the Captain dead to the world, lying drunk on the dock. But before long everything was in order and we proceeded happily on our way. One night, we are told, Fred piloted the Mary L. to Dorset, taking down a large party to a dance. While the dance was going on, Fred got gloriously drunk. When it came time to take the party back, around midnight or after, the Captain was so full he could not sit steadily on his stool behind the wheel. He was begged to let someone else steer, but, being captain, all final decisions were legally his, and he was determined to act as pilot. He got a large man to stand behind the stool and put his arms around him so as to hold him in place, and he took the boat out perfectly through Dorset Bay and the intricate narrows and down the lake. Greaves was a teetotaler and so could not rival Fred in steering drunk, but he had a tale that was of equal proportions for being remarkable. Once he was towing a raft of logs out of Rabbit Bay. Two of the worst turns on the lake are at the entrance of this bay. Greaves was very tired and went to sleep as he was leaving the bay, and when he woke up he had brought the raft of logs through the channel and past the bad turns and was clear in the lake. Another time Greaves was running a little supply boat all by himself, being captain, engineer, fireman, and merchant all in one. To fill these varied offices it was necessary for him to leave the wheel and go to the engine whenever a change in speed was called for. He had the sides of the boat near the engine so loaded with fire-wood for the boiler that he could not pass from bow to stern except by going outside along the gunwale hanging onto the deck. While he was thus making his way to the engine, he lost his hold and fell backwards into the water, but fortunately his hand caught the gunwale as he fell and he was able to drag himself out. It is interesting to speculate as to what would have happened, both to him and to the boat, if he had been less fortunate. There was a Captain Casselman who was very proud of the way he handled a boat. Mostly he worked on Peninsula and Fairy Lakes, but for a while he was on the Lake of Bays, and Greaves was acting as his engineer. Casselman liked to bring his boat into dock full steam ahead, and then at the last moment ring the bells for reverse engine and make a sudden stop. Greaves warned him that the propeller was loose, and that he might have trouble if he continued his sudden stops. But Casselman was a proud man and did not heed the warning. So, soon after, he came storming up to a dock full steam ahead, and as he ran down the side of the dock he banged the bells for full steam astern. The engine was duly reversed, and the propeller came off, and the boat ran merrily on to the beach and grounded itself. Once Fred and I took Anna and Corinne Cunningham to a regatta at Birkendale. We paddled down Haystack Bay, and picnicked on Haystack Island. After lunch we paddled on to Birkendale and watched the regatta. Then we portaged over to Marsh's Falls and paddled down the river and reached the Cunningham home in time for a welcome dinner. The exciting race at the regatta was between the steamboats, Mary L. and Florence. Off they went full speed, down the bay and around an island and back. Ramey, the fireman on the Florence, was afraid the boat would lose because the boiler would not have pressure enough with the safety valve set where the inspector had put it. He was a very fat man, and he solved his problem by crawling up on top of the deck and sitting on the safety-valve. What courage! If the old boiler had blown up he would have got somewhere fast enough, but maybe not to the winning line. Even so, the Mary L. won the race, and I can see her. yet, rounding the island so fast I thought she was surely going over. It was told about Ramey that his fat caused him to float when he went in swimming, and he could never get wet all over at once. So he tried a new scheme: he ran the entire length of a lumber barge and took an immense flying dive, only to bounce back out of the water and land feet first on the barge again. Our children loved the Mohawk Belle and Captain Tinkus, who ran it. Often the Mohawk would come in to Cunningham's dock, and from there go over to the Dwight dock. If the children were at the dinner table when the boat was coming in, they would frequently leave the table in the middle of a meal and race to Cunninghams', if the boat was headed that way, and jump on board. That meant a free ride to Dwight, and if Tinkus was in a good mood, the chance to steer the boat part of the way. There was a day, long ago, when the Mary L. was coming into the bray in the morning, and suddenly began to act most queerly. She turned this way and that. Then, before we could discover what was happening, the Florence came around the point and began doing the same, but not following the Mary L. With the help of field glasses we discovered that there were two deer in the lake and the boats were chasing them. Soon Mr. Cunningham made the same discovery, and off he was in his skiff and with his gun. He came within range and shot one of the deer, but before he could reach it, it sank, for it is only at certain seasons of the year that a deer will float, and this was the wrong season. We were all sorry to see the deer shot. And now the steamboat days are gone, and nothing will ever come to take their place - beautiful, romantic days which, like so many other beautiful things, have surrendered to what we fondly call progress!. What! No Fish? It is well known that Mother Ruth let no opportunities slip from her grasp. Once she dropped everything and went from Dwight to Rochester for a few days just because someone was going to Rochester and there was room for a passenger. In such sudden decisions she reminds one of Winston Churchill. No one set out for Huntsville if she knew it without some commission if she could find one to give, and she generally could. And so it happened that one day I was driving in to Huntsville to do some shopping. Mother Ruth heard of it and decided immediately that this was her opportunity to get some fresh fish for dinner, and at her behest father commissioned me to get fish at Armstrong's meat market. My trip was successful in every way except in regard to getting the fish for Mother Ruth. It was not fish day at Armstrong's, so I came home without any. As I drove slowly by Alderside, father began to rise from his chair on the verandah, and called, "Harold, Harold!" "Yes, father." "Did you get any fish?" "NO." "No fish?" "No, no fish." "What, no fish?" "No, father, no fish." At that moment, Mother Ruth, whose hearing was just beginning to get like father's, came through the door of the house and called, - "Joseph, what did Harold say?" "He says he got no fish." "No fish?" "No, no fish." "What, no fish?" "No. Ruth, no fish." By this time I was a little far along for further hearing, but methinks that Barbara, the cook with the wooden leg, came stamping along from the kitchen through the dining room and the living room, towards the door, joining the chorus, with a regular,- "What, no fish?" And it became a saying in that country, even unto this day, when anyone was seized with surprise and incredulity, "WHAT, NO FISH?" Isabel's Famous Trip to Dwight There are special reasons for remembering a number of different trips to Dwight made by members of the family. Harold Welch, for instance, will never forget the year of the Welches' return to Toronto from the west, when, as a rather young boy he came to Dwight to visit his grandfather. While he had been living in the west, Douglas Atkinson and I had installed a joint dock in front of the church between our places, and the Mohawk Belle was able to make a landing at it. So Harold came in on the boat, and did not, of course, recognize our dock as the boat pulled up to it. When, however, to his surprise, he saw his grandfather and myself standing on the dock calling to him to get off, he rushed from the deck down just in time to jump off before the boat pulled away. In his haste he had left his baggage on board, and he says that he never was so embarassed as he was for the next two or three days, sitting around on the Alderside verandah, dressed in his best go-to-meeting clothes, waiting for his baggage to return, and terribly afraid that all his young cousins would put him down as a sissy because he was dressed up on weekdays in Muskoka. Of all trips, however, Isabel's is the most famous. In June of 1919, as I recall, the Northern Baptist Convention met in Buffalo. It was time for Isabel and the children to go to Dwight, so I went as far as Toronto with them, and then returned to Buffalo. All went well from Philadelphia to Toronto. It was early in the season and summer train schedules were not in operation, so there was no choice, Isabel would have to take the afternoon local from Toronto, and arrive in Huntsville some time after ten in the evening. I telegraphed to the Reid House in Huntsville to reserve rooms for the family and Hazel Richardson, the maid, and with arrangements thus completed, took my train back from Toronto to Buffalo. The trip to Huntsville was broken by a very long delay at one point. When the conductor happened to pass, Isabel asked him what was causing the delay. He replied, "Well, ma'am, do you want to be ushered into eternity?" She was not contemplating any such move, but did not see the connection. "We have a flat wheel on this car", he explained, "and we have to take the car off or the whole train may be wrecked." So off came the car, and all the passengers were crowded into the only remaining car which was already filled with workingmen going north on some construction job. Isabel managed to find a single seat where she and Hazel and the children crowded in, and the children being very, very tired, gradually fell off to sleep. About midnight the train pulled in to Huntsville. Only the night clerk was in the station, and there was no bus from the hotel. Isabel called the hotel and asked about the bus. "Oh", said the clerk, "your train is so late there's no use making a trip for it. The train from the north will be in in half an hour, and then the bus will go to the station." So the weary group settled down on hard station benches and waited sleepily for the train from the north and the bus. Eventually the train came, and the passengers for the hotel were gathered up and taken to the hotel. Isabel happily anticipated a comfortable bed in the hotel, for she was almost as tired as the children. The night had turned cold, and when the family entered the lobby of the hotel there was a fire in the stove and a number of night owls were sitting around it smoking and drowsing. Isabel went to the clerk and inquired for her rooms. "Why we haven't any rooms for you", he exclaimed. "Didn't you get my husband's telegram?" Isabel asked, "Why, yes", said the clerk, "but we're filled up." "What am I to do?" asked Isabel. "I don't know", answered the clerk indifferently. Well, there was a sitting-room upstairs, and they could sit in it, if they wanted to. Just then a young travelling man stepped up to Isabel and explained that he had heard what was going on, and that he had a room which he insisted that she should take. Yes, he had a wife and children, and he would hear of nothing else than that she should take his room: he could sit up more easily than could the children. Very gratefully Isabel accepted his kind offer, and took Hazel and the children upstairs. Hazel, and another girl they had met, wrapped themselves up in coats and slept as well as they could on the tumble-down chairs in the sitting-room. Isabel took the children with her into the bedroom, and having tucked them in, she edged in herself, and then the bed broke down with a crash! Pulling the mattress off, Isabel made up a bed on the floor; and the family settled down for the few remaining hours of the night, but not before it was discovered that in the fall Isabel's watch had suffered a broken crystal - fortunately the only casualty. Six o'clock came all too soon, and it had to be six o'clock for rising, because Isabel had to dash all the way back to the station and get her trunks through customs, which it had been impossible to do the night before. So arranging with Hazel to care for the children's breakfast and for getting them to the town dock on time for the steamboat, off she went to the station, a good three quarters of a mile. There was very little time left, and to save precious minutes Isabel accepted the customs officer's assurance that the trunks would go through without examination (Incidentally, Isabel gave him a good tip). Then with care-free mind she ran for the town dock. There is a remarkable parenthesis in the story here: although Huntsville is so far from the Southern States, Isabel assures us that she was conscious of being followed all the way through the town by a negro. Back at the dock, and much out of breath, just in time for the boat to go, Isabel found her kind friend, the young travelling man on hand to see the family off. He would not allow her to contribute a penny for the room charge, and all of us have had the sense of an unpaid debt ever since. When Isabel handed the purser her tickets, he looked at them and said, "How do you think you are going to get to Dwight?" "By the boat", said she. "There's no boat from the Portage to Dwight: the summer schedule is not on yet." "How can I get there then?" said Isabel. "Oh, maybe you can find one of the Thompsons or someone else to drive you in", said the purser. At the South Portage Isabel looked for a telephone, and finding one, she called Mrs. Archie Gouldie and asked if Goldsby could come with his auto and drive the family over. She replied that she was sorry, but Goldsby was away, but maybe Jimmy Asbury could come, as he now had a car. Isabel called Jimmy. He was sorry, but he had taken his car apart and had not got it together again yet. "But wait", he said, "Vic's just putting a launch in the water, and maybe he could come." And a minute later, "Yes, Vic will go for you." The children and Hazel were all happy in the prospect of Vic's coming, and so, indeed, was Isabel. This was an unexpected treat, and sooner than they could hope the launch came around the point from the narrows and into Portage Bay. All got in, and the trip began, but not before thunder had begun to rumble, and in a few minutes rain was pouring down in a sudden shower on the utterly unprotected passengers. Isabel tried to save her summer hat but did not make much of a.success of it. At last the shower cleared and the launch came to the Dwight dock, and there stood Mrs. Archie Gouldie, a kind and motherly figure, waiting to receive the travellers. "You poor things", said she, "Come right up to the house. I've kept the rooms above the kitchen warm for you, and you certainly must need a rest." But the children and Hazel were too happy to need a rest, or drying off, or anything. They were at Dwight, and that was all they cared. Isabel accepted, however, and with an aching head and a tired body she went for a rest, then to one of Mrs. Gouldie's good dinners, which she fully appreciated as in the haste of the morning she had missed her breakfast entirely. After that, the famous trip began in memory to lose the elements of tragedy, and to appear as an amusing and highly exciting adventure. One detail may be added to the story of Isabel's Famous Trip. The steamer from Huntsville was crowded with passengers, and it turned out that there was a special excursion that day, and everyone was going to Bigwin Inn to see it, as it was just then being opened for the first time. The girl Hazel had fallen in with the night before was on her way there to work. Bigwin was opened in the summer of 1919. [Following story with picture] Yea, the sparrow hath found her a house -Ps. 84:3 and the children a play-place - Even thine altars -- Some years ago when my grandson, Gordon, was quite small, his cousin Johnny was visiting him. The two boys went with me on Sunday morning to put the last touches on getting the church ready for service. I left when the work was done, but the boys lingered behind. Soon I heard the most awful noise coming from the church and hurried back to see what was happening. Gordon was in the pulpit shouting and pounding as hard as he could. John was at the organ, pumping for dear life and pressing all the keys he could. One sight of my beckoning finger at the door, and the racket ceased. Then, as I led the boys toward the Pine Cone, the following conversation ensued:

What's in a name? Little Gig was with me near the driving gate in the side of the lot. A chokecherry tree was standing near the gate with a fine lot of fruit on it. Said Gig, "Grandpa,-whet is that?* "That's a chokecherry tree", I replied. "Try some", I said, handing him some cherries. He ate them, puckered his mouth, and ran away. Next day he found me in the same place and said, "Grandpa, get me some more of those coughing strawberries." The Great Camping Trip Long ago, when the children were little, Isabel and I decided that we would go camping and take them with us, and, as we wanted it to be an easy trip, we engaged Willard Woodcock as a guide. We were to go to Clear Lake and have a lovely time with just our own family. It happened, however, that Lois Quinby seemed much alone in Alderside, and as we were eager to nave her share our joy, we asked her to come along. After all, one more is nothing. Mother Ruth always was quick to see opportunities, and here was an opportunity. She had as her guests Dr. and Mrs. Gray from Buffalo, and their daughter, Peggy, and Peggy's fiancÚ, Parker. So she swept over from Alderside with her accustomed dignity and glamorous pursuasiveness and said, "Dear Isabel and Harold, you know there could be absolutely nothing so delightful for Peg and Park as to go with you on this camping trip. It's positively a God-send. It will simply make their visit perfect, and I am sure you would love to have them go along." Being accustomed to love what Mother Ruth thought we ought to love, we loved to have them go along, and they joyfully joined the party. Meantime I set out to get Wallie Woodcock as an extra guide, and with all this to-do the rumor of our trip had spread as far as Riverby. Now it just happened that Fred Hetherington and his wife, from St. Catherines, were visiting Fred and Hilda, and Fred and Hilda saw matters in just the same light as Mother Ruth had. So by the time I secured the second guide the Hetheringtons were enthusiastic members of the camping party. Older people's minds move slowly, and it was only now beginning to dawn on Dr. and Mrs. Gray what they were missing by staying home when absolutely everybody was going camping. Why, they would be charmed to join us, and. more than that, they would engage Pete Newton to drive them to Clear Lake in his McLaughlin-Buick, - a feat that had scarcely ever been performed before. That ought to make the having of two extra easy! "Dear Dr. and Mrs. Gray, by all means come. The trip would be almost a failure if you were left at home" - or words to that effect. Once more I scurried to get another guide, and this time found Irving Gouldie. Isabel hastily added ever so much more food to the packs, and blankets to the bundles, and eventually the expedition set out. It was a real trek to Cooper's Lake with all the canoes and packs to portage, but we were accompanied and encouraged by Ruth and Hugh, who came along that far just for the walk and to give us a good send-off. On the shore of Cooper's Lake occurred one of those incidents which only those who are at the moment free to do whatever they please can pull off to perfection. The question arose as to whether Ruth and Hugh would accompany us to the far shore of the lake. "But, how would we get back?" asked Ruth. "We'd have to walk", said Hugh. "Are you sure there is a path?" "Well, if we don't want to walk back, why not go on - there's nothing to keep us?" "But I've brought no clothes for camping." "Well, neither have I, but what's the difference? Among so many we can make out somehow." "Well?" "Well", with one foot in the canoe, delaying its start. "Well", from me, "Make up your minds, either go or stay, but we've got to get moving." "All right, let's go." I cannot describe the entire trip. It was very hot. Parker nearly collapsed at the top of a hard hill on the Long Lake Portage, struggling with a vast pack of blankets on his back. We were all revived, however, by lunch on a beautiful point on Long Lake, when the guides made tea that would stand any man's hair on end. Before we reached Clear Lake a furious thunder storm broke, but most of the party had reached shelter. Limberlost was just getting under way in those days, and as campers we were by no means too welcome. When, however, it became evident that we must hire a couple of cabins to accommodate some of our large party, the matter of camping was kindly forgotten by Mr. Hill, the proprietor, and we all settled down and had a glorious time. Dr. and Mrs. Gray, having dismissed Pete Newton and his car, returned with us through the lakes and portages, and though the paths were still wet with the rain that had fallen on our up trip, Mrs. Gray daintily stepped along and never soiled her white shoes in the entire journey. The day after our return we hung blankets on the fence to dry and air. They reached most of the way from father's to the church. Nice little camping trip, - just for our own dear little family! Well it was wonderful, and everyone enjoyed it. Linen napkins Frank Keown built the Atkinson cottage, and did a good many other things for G. D., and so he became a genuine friend of Douglas and Dora. At that time Esther, his wife, was laundress for the summer colony, and Frank knew how much work there was in keeping the community linen, sheets, etc. clean. Dora told Frank that if ever he was in Toronto, he should certainly come and visit Douglas and herself. This he did, bringing a son, or a friend, with him. Dora prepared a very nice dinner, and, of course, put linen napkins the places. When Frank sat down at the dinner, he surveyed the table, and fixed his eye on the napkin at his place and said, "We know what them is, Mrs. Atkinson, but we ain't going to use them!" Our first summer was that of 1888. Seventy-four years later Arthur and Harold still enjoy a picnic, and retain some of the spirit of the early days. On the reverse side of the picture it says, "Uncles Harold & Arthur & "Clementine". Dwight July '62." Snapshot by John (Mary's and Gordon's)- who also developed and printed it. |

||||||||||||||||

THE PASSING OF 'ARBItem from the Obituary Column of the Forest Hunter and Trapper, January 26, 1958. 'Herbert O'Toole - known to his friends as 'Arb - died at his home on Squirrel Lake, January 21.' I. 'ARB HIMSELF SPEAKS The doc he come 'bout half-past three II. A FRIEND SPEAKS That note in the paper carries me back To a day long ago, up the road. III. A GOVERNMENT STATISTICIAN SPEAKS This Herbert O'Toole - yes I knew the man. IV. THE PARISH MINISTER SPEAKS And now H.S.S. - Spring, 1958. VACATION'S END - LAKE OF BAYSI'11 not complain when the time comes at which I must return But ere And then I'll go, And when my task seems hard, H.S.S. - August 1917. |

Table of Contents

Previous: Alderside Summers

Next: The Cottages