Table of Contents

Previous: Dwight

Next: Dwight Lore

II. ALDERSIDE SUMMERSFamily life at Alderside falls into certain definite periods. First, there was the time of pioneering, from the initial family summer of 1888 to 1892, when the present front section of the cottage, including the great living room, three bedrooms, and the spacious verandahs, was built. Then followed the great period of family living in Alderside from 1892 to the interval between mother's death and father's remarriage in 1916. This was the time of liberal hospitality, of endless family picnics and expeditions, of camping trips - of which Arthur has made a splendid record - of love making, and of the marriages of Josephine and five of the six brothers. In this period, in 1906, the old log house was torn down, and the present dining room, with four bedrooms upstairs and father's bedroom downstairs, was put in its place. The present kitchen was also added, and the dormitory was swung around from being a lean-to on the side of the old log house to being a lean-to on the back of the new building. The third period extends from father's marriage to Mother Ruth in 1916 to his death in 1947. Mother Ruth had passed away ten years earlier in 1937. In Mother Ruth's regime there were many guests, but they were chiefly friends of father's and Mother Ruth's rather than friends of father's children. The children themselves were fairly frequent visitors, but to a large degree during this time they provided their own accommodations. Innisfree had already been established as a camp, but now it became a summer home for Norman and Marion and their son Eric. Then Isabel and I built the Pine Cone for our family, and later Fred and Hilda built Riverby. Arthur and Alice followed with The Cedar Chest. Meantime Mother Ruth had built Barnaby, Stony Heights, and Beacon Lodge, and frequently members of the family were in her cottages. When father died he left Alderside to Arthur and myself. It is occupied in the summer by members of the family, or by others when it is free. It is not, therefore, the family summer home now in the same sense as it was while father lived. Through the years, however, it has gathered to itself so many rich memories that it will always remain in our thoughts the symbol of family life, and as different branches of the family do occupy it, their coming to it will always seem a coming home. Mother reigned supreme during the first two periods of Alderside life. Fond memory summons up the picture of the trunks being brought down from the attic at Twenty-One Atkinson Street in Rochester(A) to be packed for the summer expedition, of mother laying some first things into them to assure us children that the time was actually at hand for going to Dwight, of the chorus we chanted for several days in advance of the trip - "Oh, the day after tomorrow and the day after that!" - of the breathless moment when Charlie Ayen's hack pulled up to the curb to take us all to the station, and of the immense wicker hamper in which was packed lunch most delicious for two days on the train, for the first day took us only so far as Hamilton, and the second day was fully occupied getting from Hamilton to Dwight. The three hundred and fifty mile trip took more time than it takes now to go from California to Italy! And that of itself made it seem like a great adventure. The first trip to Dwight was exciting, if by no means comfortable. We reached Hillside by steamer from Huntsville by about six o'clock in the afternoon of the second day. As there was no dock, we were punted to shore, as were the trunks. There stood grandfather, waiting for us, with two lumber wagons, driven, I believe, by two of the Hill brothers. All of us, including Aunt Augusta, who at that time was part of the family, were loaded into the first wagon, and grandfather rode with the trunks in the second. We had scarcely set out when a tremendous thunder storm broke over us, with a wind that made it impossible for us to hold up umbrellas. So we sat and took it, while the drivers slowly got us up hill and down dale, over roots and rocks, on the roughest imaginable road, to Dwight. Once we saw a light in a lonely cabin, and the drivers were for stopping, but grandfather would hear nothing of it. At last we came down Buttermilk Hill and along the level by the lake shore to the log house which was our destination. For years I always supposed that we arrived on the stroke of midnight, but Alex, who being older knew better, said that it was nine-thirty. Imagine our delight in finding that Mrs. Ed. Gouldie and Mrs. Schafer had broken into the house, lighted the fires, arranged shake-down beds, and made supper for us. Soon we were warmed, and dried, and fed, and tucked into bed. As I remember it, my shake-down was on the attic floor. |

The original

log house to which the family went

in the summer of 1888.This picture was taken

by Joe Humphrey in 1889.

The improvements of the

summer of 1889. On the verandah are

Grandfather, Father, Joe Humphrey, Alex and Fred.

I wonder what mother's sentiments were on that night of our arrival! I do not know.

But the following day-break might have inspired the lines of the hymn

And mother looked out over the bay and the sparkling water stirred by the breeze, with the green hills beyond and the fresh blue sky, and her heart went with her look, and Muskoka became home to her always. Years later when she went for a great trip to Europe with father, her only regret - and it was genuine - was that it would keep her from being at Dwight that summer. These early days and summers at Alderside were in many ways a time of pioneering. Ours was, I believe, the first permanent summer settlement on the lake. There was a whole countryside to explore. There were all the means for housekeeping and subsistence to be discovered, or worked out. There were all the untouched means for summer enjoyment to be realized. Everything about us was possessed by 'the glory and the freshness of a dream'. One day, very soon, some of us got as far as the swamp bridge and were sitting on one of the long pine logs that edged the road, when Alex - always an adventurer - dared us to walk to Gouldies'(A)! It was just a start of those hikes on land and canoe trips on water that took us all the way from Georgian Bay to the Madawaska River and from Lake Vernon to the far reaches of Kahweambejewagamog. Eventually Alex would count triumphantly his fifty-five and fifty-six and fifty-seven lakes he had seen - with always another yet to be explored - but the beginnings were closer home where every foot of ground was intimately known. Who that had ever known it could forget the delightful path to the top of Schafer's Hill. It took only ten minutes or a quarter of an hour to traverse it, and it offered an attractive walk after a swim in the afternoon. It came out on top of a rock at the west end of the hill from which, in those days before the second growth amounted to much, there was a good view of the lake. All along the edge of the rock there were wild gooseberry bushes. After the run up the hill we would stand there, getting our breath, looking at the lake, and filling ourselves with the sweet, warm gooseberries. Before the roads were improved, or the highways built, the settlers' cows ran loose all over the countryside. The cow-paths were a convenience and a delight: so cool under bare feet, and going so many places where we wanted to go. Old Mr. Schafer drove his cows along the path from the creek bridge to his home on the hill, and that was the best way to get there. There was a path from the far side of the bridge to Schafer's Falls on the creek, and other paths from there back and through the dells and over the hills to Cooper's Lake. There were paths all over the top of Keown's Hill, and the short-cut to the portage was largely cow-paths. In many places the wild raspberries grew thick along these paths, making a walk on them all the more attractive. |

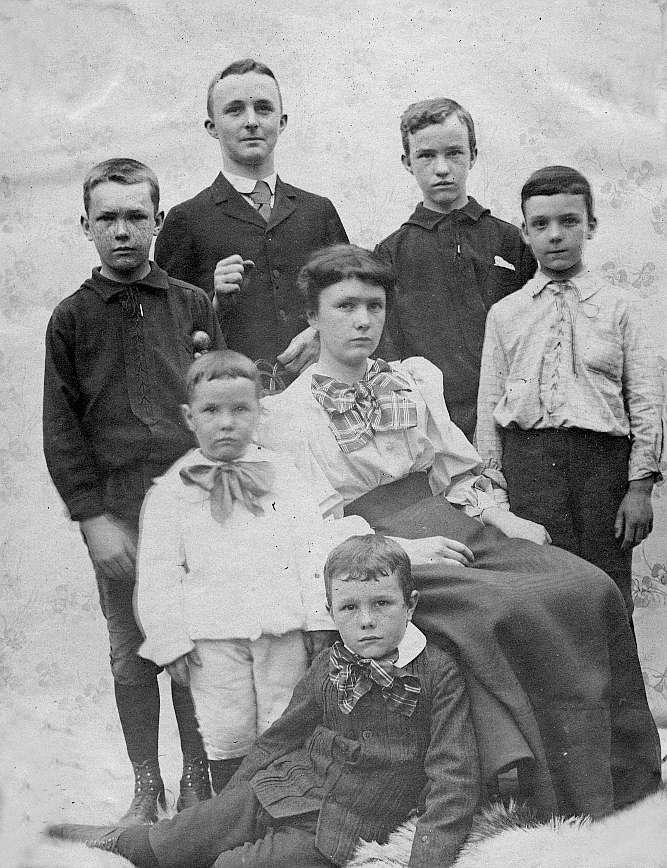

The Seven Stewarts

whom father and mother

took to Alderside in the summer. Josephine, Alex, Fred, Harold,

Arthur, Norman and Hugh. This picture was taken June 16, 1983.

Larger scan of this image (but not retouched)

Similar image taken a year or so later

| Without doubt the lake itself was the main attraction to us as children, and it remains such to us as we have grown old. Before stop-logs were put in the dam at Baysville, there was a broad sand beach in front of Alderside. One could walk on the sand to Cunningham's spring, and, in the other direction, the sand reached far out in front of the road beside the creek. In fact, Kemp's saw-mill had stood between the road and the lake, where now there is nothing but water. Day after day we played on the beach, digging canals, building castles, and wading along the shore. We had no boathouse and no bathhouse. At night whatever boats we had were drawn as far up as possible on the sand to keep them from being drifted away in a sudden wind, and canoes were always turned over to keep them dry. There was an alder growth all along our waterfront. In the level space east of our present boathouse we cut out little rooms for ourselves in the alders, and used these as dressing-rooms for bathing. Each of us - father, mother, and each child - had his own room, and our wet bathing suits were left to dry after bathing, hanging on pegs cut in the alder growth. This arrangement was immensely convenient, for we could be in and out of the lake any time in the day, when any one let out a shout, "Hurrah in for a swim!(A)" The sand beach was also our laundry at first. Father secured some woman, Mrs. Ketch, I think, at first, and maybe Mrs. Burns later, - to be our washerwoman. The tubs would be set up on the shore, and a huge iron kettle hung over a fire of pine roots and sticks and driftwood, to provide hot water, and the woman would rub and scrub till her task was done, getting fresh water from the lake, and pouring the used water into the sand. We could not be content, however, to remain on the beach with the lake luring us. The going on the water was heavy at first, for our only boat was a punt with home-made oars. But in the punt we rowed to the spring for our drinking-water. I can remember working with father to clean out the spring and put a trough in it so that we could come to the shore and get water within a few feet of where we landed. Then, often, we rowed the punt to the bluff to fish. Father got Mr. Ketch to prepare poles and lines for us youngsters, and so one day he came with a bunch of alder poles all fixed up. There were lots of perch in the lake before it was stocked with bass, and on a nice damp morning, or even on a rainy one, off we would go to the bluff. I recall going with father and old Daddy Keown, and we got twenty-two perch. The bridge was a good place to fish, too. Arthur caught a great perch there, and he was afraid to touch it, so be ran all the way home with his pole over his s shoulder, and the fish flying at the end of his line. The punt formed a good substitute for a raft at bathing time, and we had no end of fun scrambling over it. Once when we were finishing our bathing, little Norman crawled into one of the punts and got himself off from the shore. The wind was from the north and it quickly drifted him out. We were all startled. Aunt Augusta got into the other punt and stood in the bow and tried to paddle it out to where Norman was, but she succeeded only in getting her boat swirling around in circles. Finally father came to the rescue, and seizing a pair of oars he rushed into the lake and swam to Augusta's boat, and crawled in, and to the accompaniment of our shouting to Norman to sit down, he rowed out and made the rescue. Punts stayed with us till long after we got our first canoes, and it was not till we had had a skiff for some time, and the old flat-bottomed boats had grown heavy and leaky that we finally gave them up. Once during the time of punts Arthur and I actually attempted putting paddle wheels on one of them. Instead of rowing, we sat and pulled on pegs that went through the shaft. The motion of the boat was beautifully smooth, and we were proud as Punch! Grandfather used to come to Alderside in the early years. He died in 1904 and he probably missed some summers before that, but frequently between 1888 and that year he was with us. The little room back of the chimney in the upstairs front part of the house was known as 'Grandfather's room'. He did not come for a vacation. His interest was still in his missionary work among the people, and he spent much of his time doing pastoral visiting and sometimes holding services in the homes where he was welcomed. Each morning he was up early, and as soon as he was dressed he would go to the lake for his morning wash. The path from the house to the lake was quite crooked because it had to go around stumps and roots and other obstructions. From the window by my bed I could see grandfather going down the path, teetering from side to side according to the irregularities made by stumps and roots. One day I put in a lot of time making the path straight. I cut roots, and got rid of obstructing bushes, and generally did a good job in which I took a natural boyish pride. Next morning, when I heard grandfather start for the lake I leaned over from my bed and looked out the window to witness the pleasure he would take in the straightened path. I was too young to reckon the force of habit! Down went grandfather, teetering from side to side as always, and just where the roots and obstructions had been, as though I had not done a tap of work! One afternoon grandfather was to go over to Ketch's to hold a prayer-meeting in the evening. I was to row him down the two miles. When the time came to set out a fierce storm had developed with high wind and rain. Father forbad my going, and was sure that grandfather would not think of making the trip because of the bad weather. But he miscalculated grandfather's devotion to his tasks. He wouldn't think of disappointing the Ketch family! So, taking his umbrella, the old man, past eighty, marched off up the road, over Keown's Hill, along the path through the bluff woods and on to the Ketch farm. Another day I rowed grandfather across the bay to Wilder's landing as he wanted to make a call at the farm. I shall never forget how he talked to me on the way, saying how earnestly he hoped that each of his grandsons would get a good education. His own had been confined to about sixteen weeks of schooling, but he made great use of what he had. Grandfather used sometimes to come into our bedroom in the morning and rouse us up. There were two double beds in the front room upstairs with four boys in them. Sometimes he would tickle us to get us awake, and once he sat down on the side of the bed I was in and it broke down with a crash. Father had built the bedstead out of pine boards, and he was quite annoyed at grandfather's antics. One Sunday morning we were all in the little church at service, and grandfather was conducting the service and preaching, as father had not yet come to Dwight for his vacation. I can still hear his fine, rich, strong Scotch voice, full of warmth and appeal, as he preached. There was no organ in the church in those days, and at one point in the service grandfather gave out a hymn and said, "And Miss Stewart will raise the tune". We were all beginning to rise for the singing by this time. Josephine started mumbling the words as she stood up, and by the time she was on her feet she had struck into a good tune. But the trouble was that in the second and the fourth lines the tune was one beat short for the words. Each one decided for himself which syllable in these lines he would leave out, with very interesting and amusing results. When we came down to breakfast one morning we missed grandfather. A little later I went for the mail, and when I was near Gouldies' I met him walking towards home. "Why, grandfather, where have you been? We missed you:, I said. "Well", he answered, "when I woke up I didn't feel very well. Then I thought about Mrs. Robson, who is dying, so I decided to go over and call on her. When I got there she was lying in her bed, smoking her pipe." He had gone off without breakfast, because he did not feel well, to walk four miles to Robsons', and here by the middle of the morning he was almost back home again. I think he was past eighty then. Grandfather was proud of his fine head of pure white hair, which with his white beard coming down the sides of his face and under his chin, was quite impressive. He liked to get mother to cut his hair for him. Dean Burke of McMaster University told me that when he was a small boy he always thought of God as having a head of white hair. Once grandfather came to preach in the church which he attended, and when this old man with white hair appeared in the pulpit, he said to himself, There, I guess that must be He!" Father said that when grandfather ceased to eat three good platefuls of oatmeal for breakfast he knew he was getting old. So he was, but father has also recorded the fact that after grandfather was ninety he gave an historical address in the Presbyterian Church at Durham. He was not, however, to reach ninety-one. He fell sick, and was in bed, but was still determined to get up and preach. "But I will preach", he said to Aunt Augusta. He did not, however, get further than the floor in his determined effort, and Aunt Augusta had to help him back into bed. How much of our life at Alderside we owe to grandfather. It was he who first went to Dwight. It was he who bought the first acre of land and the log house, and later gave it to mother. It was he who founded the church which has always been a center of our interest and joy, and it was he who met us at Hillside with horses and wagons and drivers to take us on the last lap of our first journey to the Lake of Bays. |

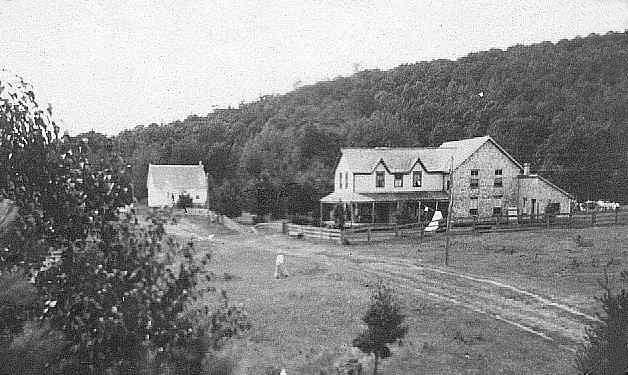

Alderside and the

lake, seen from Schafer's Hill, after the addition of 1892

[On far shore: Oxtongue River mouth at left

and Ruggles Bay entrance at right -- JSA]

Enlargement from this image, annotated

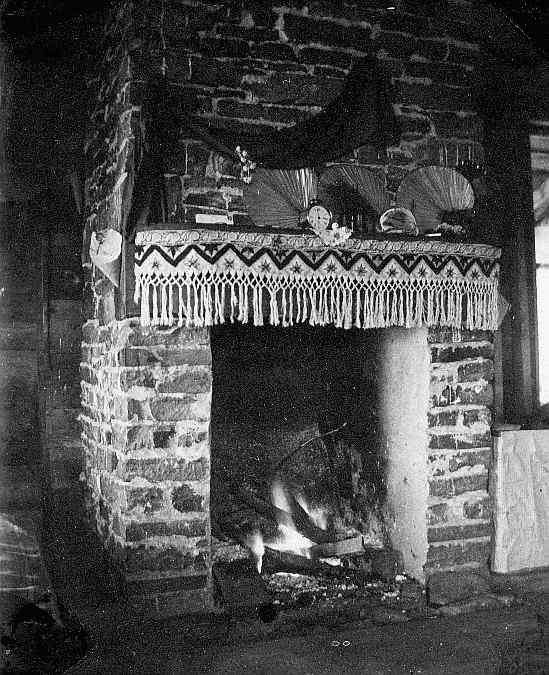

The fireplace -- taken by Joe Humphrey

in the summer of 1892.

[The fire hazards in this photo give me the shivers! -- JSA]

More detailed description of this image

| Father's interest in Dwight began when grandfather invited him to assist in the

dedication of the church in the summer of 1887, and his concern for the church never

flagged. While he became immediately interested in the place as a summer home for the

family, the church was always a major responsibility, and he preached in it every summer

and conducted the worship every year but one for fifty years. One summer he and mother

went for a trip to Europe. For two or three years the Dwight church was a summer field for

a McMaster divinity student placed there by the Home Mission Society. But when it became

evident that father would be on hand each summer to conduct the worship and preach, the

Society left the care of the church entirely to him. On occasion he brought to the pulpit

of the church men of genuine stature such as Chancellor Whidden of McMaster University and

Professor Walter Rauschenbusch of the Rochester Theological Seminary. Mother Ruth once

remarked that she didn't mind Sunday, but she didn't like to have it start Saturday noon.

But that's when it started with father. There must be quiet for his final preparation, and

the church must be put in perfect order, and it must be early to bed Saturday evening. But

this summer ministry was worth it all, as hundreds of people would testify. It helped to

form the character of Dwight as a summer resort, for many summer visitors came in part

because they were assured of the quality and worth and dignity of the Sunday morning

service in the little church, and they were never disappointed. It was father who secured

the chairs that took the place of the first crude backless benches, and later the pews

which replaced the chairs. It was he who got the Pratt men to build the seat around the

wall. He always looked after the painting of the building, the fencing and care of the

lot, the cleaning of the sanctuary. He secured the organists, and often the special

soloists, and he encouraged four of us boys to sing in a quartette every now and then.

Father himself gave of his best in his preaching - and it was great

preaching. Everything in the service was done with dignity - a dignity suitable to the

Victorian age which continued more than a dozen years after Alderside was established. I

can remember in the first years seeing father march into the pulpit in the little church

wearing his Prince Albert coat and a stiffly starched white shirt and winged collar, while

the humble congregation - mostly settlers in the first years - in the rough clothes their

backwoods homes afforded, sat patiently on the backless benches. The frock coat

disappeared from the Dwight scene after a few years. The dressing up ended, however, with the Sunday service, and for the rest of the week in the early years, father was truly a pioneer summer resident, and much of his fun was in the pioneer task. The summer of 1889 saw the adding to the log house of a neat verandah across the front, and about the same time, of a lean-to (the dormitory) on the east side. This served well for a couple of years, but by 1891 father was busy planning with William Ketch for the present living room, front bedrooms, and verandah. William Murray did most of the building. Father himself built some of the bedsteads and saw to it that we got straw for the ticks. The owner of the sawmill that had stood by the creek had left the ground covered with great pine logs, their stumps everywhere deeply rooted in the ground. Father organized and supervised bees for dragging the logs together for burning. He got Tom Burns from up the river to come and dig and cut out many of the stumps. We boys took a lot of pleasure in burning stumps. Smoke from the fires went up day after day as it often took most of a week to get a stump really burned out. One summer at the beginning of our going to Dwight father had a large tent erected in front of the log house, and several of the family slept, or swatted mosquitoes, in the tent. There were more mosquitoes in the early days. Often in the evenings we filled smudge pans and lit them and smoked the mosquitoes out of the bedrooms before retiring. Father could never see things untidy. and he was often busy with a rake making the place look neat. A few years before he died I found him out by the wood pile raking, as he so often did. As I came along he paused , gave the lake a sweeping glance, and said, "Well, Harold, we go to the city to do our work, but here's where we live, isn't it?'' Putting things in order extended beyond the Stewart property, and it was father who took the lead in organizing a Cemetery Association and getting the burying ground properly laid out in lots and cleaned and fenced. He got up a bee to paint the church - of course everyone who came ate at our house - and he encouraged the men of the community to clean up the lake front and to make walks along the roadside at Dwight. Picking berries, bathing, and going for walks and picnics were constant recreations. Father was always a leader in going for raspberries when the season was on. He loved to get us all out, each with a cup, and someone with a basket, into a good patch - maybe over towards Ketch's farm, or in what we called Raspberry Valley on the east side of the creek, or over at Flemmings - to spend an hour or two in the warm sunshine gathering berries for the table, or for jam. We were not all equally good at the task, and Alex produced more homespun philosophy on these expeditions than berries. But Alex made up for that by his skill with an axe, and a good many huge dead pines that marred the landscape fell before his sturdy blows. There was one at the top of a high bank along the creek towards Schafer's Falls. Alex cut it, and when he had it ready to fall we all gathered to see the immense splash as it crashed down into the water of the creek below. I do not remember a single live original pine along our shore, but there was a number of dead ones. This condition was probably due to forest fires. As the years went on summer visitors began to multiply. The Charles Cunningham family from Rochester took the property around the spring. M. S. and D. K. Clarke came, camping on Stony Point for a few years, and then building west of the Cunninghams. And then others followed. But before Dwight became the resort that it now is, the Sunday Night Sing developed at Alderside. First it was just the family who used to sing together Sunday evenings, then the family and the Clarkes, and then all we could gather together in those days when we knew every summer visitor. We would sit on the verandah on balmy evenings, or in the living-room around a bright fire on cool evenings(A). Father would lead with his splendid voice and his wide knowledge and deep appreciation both of hymns and tunes, and each one who chose to would call for his favorite hymn. I can remember an evening when there were more than forty gathered together in the living-room. But what I remember more is the beauty of the hymns we sang, and the lasting impression their words and their music made on me. "Jesus, still lead on", "Beneath the cross of Jesus", "Lead kindly Light", "Jerusalem the golden", "For all the saints" - these were among the favorites. We sang them Sunday evenings with our friends. Then, often, we took some of the guests home, usually by canoe. What a perfect ending for a Sunday! The sings are something never to be forgotten, even though they can never be revived because they belong to pioneer days and to a different atmosphere from that in which we now live. Alderside became a symbol of hospitality. Both mother and father loved to have visitors. Arthur records the names of more than seventy-five guests through these years, and there were many more included under the term 'record incomplete'. Father had a certain pride in the place - it was the only property he ever owned - and he wanted his friends to see it and enjoy it. So, almost from the first, and especially after 1892 when the house was expanded, there were visitors every summer. Some were friends of mother's and fathers, and many were friends of us children; sometimes they came as family groups, and sometimes singly; some came once, and some came repeatedly. All were welcome. Deacon Charles Matthews, being one who came in 1889 as almost a first visitor, built us a ten foot dining table, and after 1906, when the new dining-room was built, we sometimes had to add another large table to accommodate everyone. One summer there were thirteen people in the house all the season, and for one week, at least, there were seventeen. One night there were over twenty. The list of supplies for the summer read like "Solomon's provision for one day" described in the fourth chapter of First Kings. As I recall, we took seventeen large loaves of bread from the baker one week, when he used to deliver it. Lamb came from William Thompson's. One summer he brought three hundred and seventy-six pounds of it. Old Daddy Keown brought milk, and one summer he brought five hundred and twelve quarts. Mrs. Ketch supplied most excellent butter. So it went. I have no idea how father stretched his minister's salary to cover all these items, and all the railroad tickets for all the Stewarts each year. That was a question of no concern to the happy family, or for the hosts of visitors. Usually the family would go to Dwight in advance of father. He would arrive about the middle of July. Once when he was making the trip he sent a telegram to mother stating the time of his arrival. When he got as far as the Portage someone said to him, "Are you going to Dwight?" "Yes", said father, "Well, said the man, "there's a telegram been hanging around here for a couple of days for someone at Dwight. Could you take it in? The boats aren't going in there today." Father was glad to do it, and he got a buggy to drive him to Dwight. Arriving at Dwight, at the Alderside gate, he handed the telegram to mother, to whom it was addressed, telling of his coming, and then got out of the buggy - thus duly announced - and arrived! |

Alderside after completion in 1908 - the church in the distance

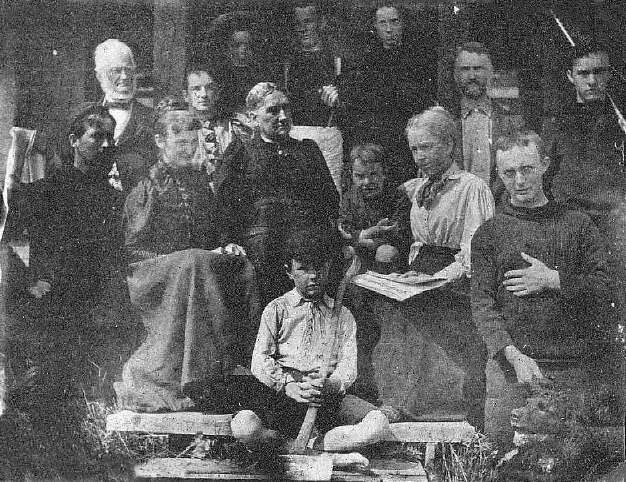

The House Party, 1895. In addition to

the family there are

Mrs. E. R. Andrews, Miss Kate Andrews, Grandfather,

Joseph L. Humphrey of Rochester, James B. Arnold of Rochester,

and the dog from Heaven knows where.

Identifications by Alexander M. Stewart and John S. Allen

| When father came to Dwight in the summer after all the rest of us

had arrived and been enjoying our vacation for most of a month, he often brought something

to help the stock of food. Usually it was a couple of baskets of black currants, which

could be made up into jam for the family. Then for half a day after his arrival we all sat

on the verandah and picked the currants from the stems in preparation for the jam making.

It was not, however, only getting food that concerned father and mother, but keeping food

fresh after we got it. A big cupboard with screened doors in it was built, and it served

well for keeping bread and dry foods sweet and fresh. Then father had a large root-house

dug underneath the dining-room with an entrance from outside. This was good for potatoes

and vegetables but it did not solve the milk and butter problem. Finally. one year, father

got Mr. Ketch to build an ice refrigerator and an ice-house. This took care of things

pretty well for many years. At first the ice-house was located on the embankment towards

the lake in front of the cottage - this for convenience in filling it with ice in the

winter. But there were two objections to this location; one was that it got sunlight on it

from dawn to dark and its store of ice would be melted before the end of the season, and

the other was that the ice from its supply had to be carried so far to the refrigerator.

So one day, in characteristic fashion, father organized a bee for moving the ice-house(1). It was a great day, and all sorts of difficulties were encountered,

but eventually the ice-house settled down in a-more shaded spot not far from the kitchen

door, where it did valiant service until the introduction of the very modern electric

refrigerator. Father lived through all the years of mother's regime at Alderside, and then twenty years while Mother Ruth held sway, and then ten years more. He came to his beloved summer home most of the last ten summers alone, and had company visiting, or else just enjoyed being in the house alone with faithful Bella Quinn to look after him. He would sit quietly by his fire, or in the sunshine on the verandah, and read and chat. Members of the family who had built cottages were close at hand; neighbors would drop in, and summer visitors passing on the road would sometimes come and chat with him. He loved to look at the pine trees which, as second growth, he had watched develop for move than a half century. Each year they seemed larger and more beautiful to him. What long and happy memories went through his mind as he gazed out at the bay, or followed the slow sunset. It was enough just to read, to chat, to look, to think, and to remember. And when the time came to depart from it all, he could well say, as President Eliot of Harvard said when he turned his boat away from a Maine coast island, "What beautiful things we leave behind." It is an interesting fact concerning mother that while she must have had endless duties associated with housekeeping, the impression she left was of one who was always free for other things. The housekeeping was wonderfully done, but it never seemed to intrude itself on the other aspects of her summer. Mother was somehow always free and ready for a canoe ride, a picnic, a walk, or even a camping trip. I remember at least twice when she went with the family camping, and before we were old enough to go, she went with father and a company Ed. Gouldie got up to spend a couple of nights on Long Lake. She came home over and over again from these expeditions with some beautiful or interesting thing she had found and picked up, it might be squaw berries, or Indian pipe, or a bit of quartz. One summer we had Eliza Stout, an Irish woman, as our maid and cook. When she saw mother coming home one day with her hands full of her treasures she exclaimed, "Ah, here comes Mrs. Stewart with some more of her trash." It was this same Eliza who gazed in amazement at all the lakes on-the journey in from Huntsville and said, "My land! what a lot of water!" A family picnic always meant a fire on the shore somewhere, over which water was boiled for whatever hot drink we had. At first, when we were children it was always cocoa, for we were considered too young for tea or coffee. Mother would see to it that the big iron pot and a lot of milk and sugar and a tin of Cowan's Cocoa went in one of the boats to the picnic, and no cocoa ever tasted better than what mother made over those picnic fires on a sand beach, or on a rocky point - where ever the picnic was held. As we grew older we went further afield for our picnics, to Haystack Island, or "The View" on French's Hill, or to Hummie's Point(A) - now Point Ideal. At the latter place we had a picnic one day, and a fierce storm of wind and rain descended on us just after we got beyond Poverty Island. We kept paddling on through the rough weather, and then had a lot of fun building a roaring bonfire and eating our lunch standing around it drying off. All the boys will remember how mother never wanted to go in a canoe on a trip merely as a passenger. Always she wanted to do her bit, and she persisted in this until her efforts were a mere dipping of the paddle into the water in time with the stern paddler. Mother used to say that if Gouldies lost their weight for the scales at the store she could substitute for it as she weighed just one hundred pounds. She loved to go for a dip in the lake before breakfast, even though it took her quite a while to get really warmed up after it, specially towards the end of her life. She never surrendered to the idea that she was not strong. Even the last summer of her life she set out with father and me to walk over to Innisfree to see Norman and Marion, and turned back from the top of Keown's Hill only because a storm broke on us and it began to rain. Our Sunday afternoon walks were a particular joy when a number of the family would go together and mother would interest us in the things in nature we were seeing, or in the thoughts that were stirring within her. Not all our picnics called for boat trips. We sometimes went by land. Once we went to the top of Blackwell's Hill dragging our supplies with us. The inducement was the glorious view across the land and down the Lake from that point. Second growth has doubtless robbed the place of the view by this time, and has made it almost impossible to find one's way up to the top. Another time we went by wagon to the Wells farm. Father and mother were walking behind and I ran to jump up on the wagon. As I was poised over the back of it, father called to me to say that I reminded him of the small boy whose trousers were made mostly of fresh air. Another time we went to Oxtongue Lake, eight or nine miles away. Mother walked most of the way as the ride in the wagon was so rough. She had put in china cups and saucers to use at lunch, and they were packed in a basket in the wagon. At one point it was necessary to drive over a thick butt of a tree that had been blown down across the road. When the cups were unpacked every one of them had the handle broken off it. Many times mother was the organist in the little church, if Josephine was not on hand to play. And she made a custom of gathering flowers and arranging them for the pulpit. In this service she was followed first by Carrie Quinby, and later by Isabel. Mother's interest in people took her often into the homes of the settlers. She was with old Mrs. Keown as soon as she knew that old Daddy had died, and came back to tell us that Mrs. Keown's lament consisted in saying, "He was a tall old felleh." She was with grandfather at Charlie (Sr.) Thompson's wedding, and acted as grandfather's clerk. When grandfather asked Charlie how old he was, Charlie turned to his mother and said, "Mother, how old am I?" to which she answered, "Charlie, you be 30 years old." "Gosh", said Charlie, "I never thought I was that old." One day after the very numerous Hood family had settled across the creek where Bill had established a store; mother heard screaming, and. supposing that one of the Hood children had fallen into the water and was in danger of drowning, she set off on a run to the rescue. Alex saw her, and quickly tore the rules for resuscitation from the wall where they were fastened, and raced down the road after her calling, "Mother, mother, here are the rules for resustication", to which mother panted back, "No, Alex, resuscitation." Arrived at the Hood door mother inquired from Bill, who met her, if any of the children was drowning(2). "Oh, no", replied the smooth Bill, "I was only thrashing my wife. Would you like to come up and see her?" Mother was not very sure, but she bravely followed Bill upstairs to the room where Mrs. Bill was tied to the bed. "You see", explained Bill, "she tried to shoot me, and so I am punishing her." "Now, Bill", said she, "you know very well it was only once, and then the gun wouldn't go off!" Bill was an odd genius, an excellent guide, marvellous in a canoe, clever, gentlemanly when he wanted to be, as dishonest as possible, sometimes cruel, the typical villain both in looks and behaviour, a man of bad reputation. He finally cleared out and left his family. The last I heard of him he was making his living by acting as an evangelist on the Pacific Coast. Rumor has it that he returned to Ontario and died somewhere north of Huntsville. Rising fog, mist on the lake, an aurora, drifting clouds, sunset, moonlight on the water - these all fascinated mother. I recall one night when we had returned from a tea at Birkendale, as we alighted from the conveyance that brought us home, we turned, not into the house, but towards the shore to stand with mother and gaze at the unusual beauty of moonlight on drifting fog over the water. Maybe because there had been a telescope in her early home, mother was particularly interested in the stars. Often on clear nights she pointed them out to us, naming the great ones and the constellations - Vega, Arcturus, Antares, Capella, Cassiopeia's chair, Draco, and many others. Once she organized a party on the verandah at three o'clock in the morning to view one of the planets that was particularly brilliant at that time - I think it was Neptune, or maybe Mercury(A). And when the days were chilly, or the nights dark, there was the fireplace, and the fire, and there were good books. I cannot recall my mother ever reading a book of inferior quality. Frequently there was reading aloud, and the picture remains still clearly in mind of the family sitting around the hearth in the glow of a fire of pine knots, listening with facination while mother read to us. Maybe it was Drummond's French Canadian poems, which she did perfectly, or maybe it was Tennyson's "The Passing of Arthur". When it came to the lines,

- well, we had not gazed at moonlight on the white fog by the margin of the lake for nothing. It might all be happening now just outside, down by the creek "among the bulrush beds" that Sir Belvidere threw the sword, and

The reading gave great things to dream about when we finally made off to bed. Fortunately, mother left her own appreciation of the countryside. I am not aware that any of her poems that have been preserved grew out of her experience at Dwight, but she wrote the following article for The Post Express of Rochester, N.Y. some time in the early years, and much later it was copied into the Forester of Huntsville, issue of June 8, 1933.

When the family went to Dwight for the first time in 1888, Josephine was a girl of twelve, Alex was a tad of ten years, and the rest of us strung along down to zero - which was Hugh's age! It will be seen that the adventures of the early years were only such as very young folk could undertake. Hugh was born in the summer of 1889, and the next summer when he was taken with all the rest of the family to Alderside, he took his first step on the Alderside verandah, much to father's delight. With all that there was to be done, and with all the tempting prospects the land and lake offered, we were not long making starts at adventures. We began to learn to swim, and to row, and soon to paddle a canoe, and our walks lengthened out. Father tried to teach me to swim, but did not make much progress until one day when I was tempted to follow the older boys running saw-logs on the creek. I got to one, and could not make the jump to the next, nor to the one behind, so I ran the length of the log towards the shore and jumped where I could see bottom, and where I thought the depth would be about to my neck. Alex saw my cow-breakfast hat disappear below the surface, and when I came up I struck out for a log on shore, and never after that had difficulty with swimming. Going for a walk was one of the pleasures of life. We were always fitted out with knives and cut canes for ourselves, or sling-shot crotches, or any thing else that suggested itself. It was always convenient to be able to make shavings for starting a fire. Once I actually shot a squirrel with a slingshot, but that, I think, was mostly a matter of luck, as was my killing a porcupine by throwing a stone at it from a long distance. I am certainly not so good a shot by nature! Our walks early took us to Marsh's Falls, or to Cain's Corners, or over the short-cut to the Portage to see the other Stewart family from Rochester (no relationship) who for several summers came to Jockey Henderson's hotel. There were six boys in that family, and there was a good deal of going back and forth. For several summers, later, members of the John Stewart family were among our guests at Alderside. As time went on we took longer walks. Three I recall specially: one was to Goose Lake, where we took a swim by the side of the road; another was all the way around by the Emberson farm, to the south shore of Clear Lake - where we ate and had a swim on to the Quinn Settlement on Long Lake, down the side of Long Lake, across the portage to Cooper's Lake, around it, and so home; and once we went fishing up the river with Rev. Wm. F. Kettle and got all the way to Robertsons, on Oxtongue Lake. Strangely enough, when Mrs. Robertson came to the door of her house she recognized Mr. Kettle as one of a family she knew in Glasgow. "I should 'a known ye by your nose!" she said. Josephine was exceedingly steady in a canoe. Bill Hood had a little twelve foot canoe that was quite round on the bottom. Father got seated in it and held on to the wharf, and that was the best he could do. But Josephine could kneel in it and paddle it quite easily. But with this ability I do not recall her ever going on a canoe trip, or out to camp. George Welch came along too soon, and he managed her canoeing for her after that. By 1894, however, we boys went camping. Father got Greaves Robson to take us, and we went to the Long Lake Hunting Camp owned by the Dwight-Wyman group. Greaves was an excellent guide, and had been a good cook, but had forgotten a good deal of his art. He put three handfuls of tea into the water to make tea, and when it came to pancakes he put three handfuls of baking powder in and they rose to be two inches thick. Greaves was surprised, but he renamed them Choke-Dog and they went very well. On our second day at Long Lake a number of young people came out from Dwight to join us for one night, and Josephine was one of this group, so maybe I should say she went camping after all. Greaves took us the next summer to Crozier Lake. We camped the first night at Dorset, and while he was splitting some wood, Greaves swung the axe, which glanced on the wood and cut through his shoe and into the bone on the side of his foot. At that he sat down and began to laugh. We all asked him in amazement what he was laughing at, and he said he had been splitting wood all his life and had never done anything like that, and it struck him as being funny. We bound his foot as best we could, and the next two or three days he did all the heavy portaging of the canoe, limping on his injured foot. When we got home to Dwight, mother kept him at the cottage for a week getting the cut healed.(3) Being thus initiated into camping by Greaves, we set out on our own. Arthur has recorded sixty-six camping trips by members of our family in the next twenty years. In one trip or another we covered the ground from Georgian Bay to far back into Algonquin Park, and from Lindsay up to Sand Lake and the Big East River. Alex was the greatest camper: his name appears in connection with twenty-nine of the recorded trips. Norman comes next with twenty-six; Arthur next with seventeen, Fred with sixteen, myself with fourteen, and Hugh with twelve. It must be said about Hugh that he was too young for the early trips, and if the record were extended further it would doubtless be found that he was in a class with Alex and Norman. My greatest trip was in the old bark canoe, the Sarah Jane, from Dwight to Sugar Loaf Island on Lake Joseph. Another time I went to White Trout Lake in Algonquin Park. There we ran out of food and had to turn back. After one day largely on a diet of wild boerries we reached a store where we were able to stock up again. On our second trip with Greaves we used a home made oil-cloth tent. Garson's in Rochester had used immense oil-cloth signs to advertise some special sales, one being emblazoned with the words 'Fortune's Crowning Diadem'. It was this sign we secured through Mr. Arnold - Jimmy's father - and made into a tent. First we pitched it down near the shore to try it out, and several of the settlers thought we were going to tell fortunes there. Grandfather did not entertain this idea, but he was none the less consumed by curiosity when on his way home from prayer meeting at Dwight he saw the tent down by the shore. There were four of us in it, two with heads east and two with heads west. Grandfather came stumbling down from the road and walked along the east side of the tent stepping heavily on our feet and heads which, of course, he couldn't see, and made his way to the open door and looked in. "Oh", he exclaimed, "I see you're lying heads and tails." And with that he stumbled off quite content. None of us was a superlative swimmer, but more than one swam from Cunningham's dock to the Gouldie dock - between half and three quarters of a mile. Norman was a good diver, and we sometimes went for diving to the creek bridge. It was fun going off the rail. Bonfires were more numerous than we could record specially in the early years. Every picnic had its bonfire, and often in the evenings we made big fires on the shore and sat around them and told stories and sang and roasted potatoes. It is strange now to have to ask permission from the fire-warden to have a fire. After some years we conceived the idea of having fire-rafts. This was before the number of motor boats made such an undertaking dangerous. We would build a big raft, pile it high with driftwood, and haul it out into the lake. Then as the sun went down we would call everyone possible to come, and light it and float around it, singing in its glowing radiance. One of the pleasantest recreations was taking the girls for a paddle in the evening. The trouble was there were too few canoes, but the ones we had worked hard. And this was profitable, for gradually it led along to love-making. George Welch came to camp at Dwight, and his canoe acquired a twist in the bow, so that without his direction it would head for our place. Of course he and Josephine got married the next spring. Alice and Isabel Matthews came to visit, and while Isabel says she was never in a dry canoe all the time of her stay, that did not matter, and Arthur and I found two of the best wives in the world. Hilda came up to Dwight to sing in the church. Fred paddled her up from the Denovan cottage on the South Shore. That led to another romance. Norman and Marion had lots of canoeing before they were married. Everyone else wanted to take Marion paddling, so Norman had to work hard, but he was entirely victorious in the end. Alex brought Helen to Alderside just to get in the requisite amount of canoeing before he was married. And finally Hugh met Ruth chiefly at Alderside. Right next door to us in Rochester was the Quinby home. After mother was gone father and Ruth Quinby were married, and Mother Ruth, as we called her with genuine affection, came summers to Dwight. This was the beginning of the third period of Alderside life, and naturally it differed considerably from those which went before and the time that followed. It was a great and happy time with characteristic marks and outstanding events, and it could never have been at all without Mother Ruth. Her coming into the picture brought new life and zest into father's days, new development of Alderside as a summer home, a new group of guests to enter into its enjoyment, the building of three cottages, many social events in audition to the usual round of picnics and swimming and canoeing, and a fresh and vigorous centering of the family life around the old cottage. All of us came to love Mother Ruth deeply, and, while we thought of our own mother almost with reverence, we held her in an affection that gladly accorded to her the name, "Mother Ruth". Mother Ruth was handsome, strong, and undaunted, and she had an excellent sense of humor. All this carried her bravely through the period of readjustment in which the multitudinous Stewarts learned that Alderside under Mother Ruth's regime was not quite the same as Alderside under mother's regime, and that now there could not be the same sense of ownership of everything connected with the place that there had been while mother lived. Mother Ruth came through with flying colors, establishing herself in her rightful place firmly, and at the same time retaining and increasing the loyal affection of those who had to realize that things were different. The new regime brought new faces into the Alderside picture besides Mother Ruth's. Carrie Quinby, her sister, and Lois, their adopted daughter, came immediately. Then, in different summers, another sister, Mrs. Scrantom, and a brother, Captain John Quinby and his daughter, Bessie, and others, were visitors. Caroline Quinby became 'Aunt Carrie' to all the younger members of the family, and was loved by all. She entered into the life of the community, teaching Sunday School in the then Presbyterian Church, gathering and arranging the flowers for our church, and interesting herself in the children of the neighborhood generally. She spent the summers of fourteen years from her first coming to the time of her death, as a member of the family at Alderside. Father's record speaks of her as 'Sainted Caroline Quinby'. To all the grandchildren. Mother Ruth was grandmother. Indeed many of them can remember no other grandmother, and their attachment to her was genuine. No one else ever did the things she did for their amusement. One day she was waking along the road with father. She was dressed fully in white and looked immaculate. She came with father gracefully stepping along (she had taught dancing for years) to the top of the bank in front of the Pine Cone. The children were all in for their afternoon swim. Mother Ruth paused and looked down at them. "How's the water, Paul?" she celled. "Just grand", came the reply. "Aren't you having a lot of fun)" called Mother Ruth. "Yes, yes", came the answers. "I wish I was in with you", said Mother Ruth, going slowly down the steps to the dock, carrying her parasol over her head to protect her complexion from the sun. "I think I'll come in and swim to Dorset." "Ruth, Ruth", called father, too amazed to comprehend fully what was happening, "Tut, tut)" But Mother Ruth was undismayed. She walked deliberately to the end of the dock, and, tossing her parasol to the children, off into the water. and began to play and swim with them. Such a grandmother!(A) Then there was the day when Mother Ruth and a visiting friend played witches for the children. It was bathing time, and the children were all playing around the dock in front of the Pine Cone. Mother Ruth and her friend dressed all in black, with black leggings, and black stockings pulled up over their arms. They blackened their faces. They got scarlet curtains which they waved as long streamers behind them, and, coming around back of Barnaby so that no one would see them, they rushed down Barnaby Lane screaming and hellooing, down the steps and into the water where the children were. The children were wild with excitement rind fun, except little Harold who was quite scared at such a performance. Towards the end of the First World War there were ever so many blind soldiers in Canada. Mother Ruth felt that something should be done at Dwight to provide funds to help them, so she organized a tea and invited everyone she could think of to come. The younger folk about the place were encouraged to get up stunts to raise money. The best of these was a jinrikisha ride. The jinrikisha was improvised from an old buggy, and for ten cents one could ride from Alderside to the bridge and back. It was busy all afternoon as the people of the community - settlers and summer-folk - came and went. Inside the house delicious tea and cakes were served. Mother Ruth was a great success at enlisting help, so goodies came from all sides. Isabel offered to make a cake, and Mother Ruth doubled the size she intended to make. She herself plunged into the preparation of things needed - tea, punch, decorations - with great energy and ability, and after a furious morning of getting ready, she appeared, immaculate in white, queenly in bearing, and perfectly at ease, to make everyone feel perfectly at home on the great occasion. The tea was a grand success, and a considerable sum was raised for the blind soldiers' relief. The tea was repeated the following year also. As a punch bowl was needed for such affairs, Mother Ruth carried an enormous one from Rochester with her on the train - part of the way, at least, probably through Customs - on her lap! Lois's wedding was another great event. The little church was made glorious with countless daisies on the platform and in the windows. Barnaby Lodge was readied for the reception. All the Quinbys possible were present from Rochester. The whole countryside was invited. It was a beautiful affair, and the reception was a roaring success. The bride and the groom were in swimming as the early guests began to arrive at the church, but they managed to make it on time. At the reception George Down stood with a friend near the punch bowl gulping down glass after glass, and remarking, "By George, we could do with some of that in a hay field on a hot day, so we could." The enthusiasm of the guests made it like the wedding feast at Cana in Galilee in this that fresh and unexpected punch had to be improvised in the kitchen all afternoon. At Alderside sometimes there were little card parties when players could be found, and many occasions when there were guests for dinner. Among these were frequently Mr. and firs. Joseph Tapley and little Violet. Mr. Tapley had come from England after a great career as an opera singer, and had settled on Haystack Bay. Coming to Alderside was a welcome social event for him. Once in a while father would tempt him over to the church where he would play and sing just for father's benefit. The rest of us, being well advised in advance, might hide outside and listen. Mother Ruth took a special interest in Violet.(A) Then on rare occasions, when there happened to be guests, such as Professor and Mrs. King Moore of the University of Rochester, who could dance, there was a little dancing in the old pace. Mother with looked forward to King Moore's coming, for she loved to dance, and the Stewarts afforded little incitement to it but, as she said, King Moore danced divinely. "An' she wuz right, fer she knew." One evening Mr. and Mrs. Loughery were guests at The Pine Cone. They had come from Philadelphia for a visit. The children were playing records on the little Victrola when Mother Ruth came in through the kitchen door. The record was a dance. "Come, Mr. Loughery", said she, pushing the furniture out of the way, "let's do the Cake Walk." Up he jumped and joined her, and as the little Victrola played along, they did a beautiful Cake Walk from end to end of the long room, with a lot of nigger talk(A) thrown in. Always Mother Ruth had a good story, or an apt reminiscence, to suit the occasion. Her telling was the best part of any story. One went like this: "Two little children, one a little girl and her littler brother were descending in the elevator, and it was crowded. They were pressed against the back wall, the boy almost smothered behind a huge woman. Suddenly the woman cried out, "Let me off! let me off!" She rushed from the elevator at the next floor. The rest of the passengers were greatly puzzled as to what had happened to the woman to make her so excited, till the little girl said in a quiet, solemn tone, "I know what. was the matter; Willie bit her bum!" The before-breakfast swim was faithfully maintained, even one year when the vacation extended into the cool area of September. One cold morning George Keown was passing as Mother Ruth was splashing in the lake. "Good mornin', Mrs. Stewart", called he to her, "I tell yez if yez keeps on with that I'll be cuttin' yez out of the ice one of these fine mornin's." So the seasons went on, and with the passing they became quieter. Lois was gone, and Carrie was gone and there was some sadness in all the recollections that Alderside brought to father and Mother her Ruth. Still there was the occasional guest, and the warm glow of the fire-side, and the pleasant activities that are forever associated with the place. No longer, however, were there daring walks to Huntsville , nor great undertakings like building cottages, or making four hundred pounds of old hotel carpet into comfortable rugs and carpets for Alderside and Barnaby Lodge. "I'm getting to be an awful old thing", Mother Ruth would say in fun. Then the summer of 1937 arrived and father came alone and sorrowful to the beloved place. We laid her ashes beneath a little stone marker in front of the great gray stone that stands in the quiet resting-place of our loved ones. Mother's ashes are there, and Mother Ruth, too, has fared on and left only the sweetness of memory. Father's passing ended the sixty long years in which he had constantly been the 'man of the house' in the lovely summers at Alderside. For years before his going he had been planning the destiny of the place he so much loved. In the end he left the place to his sons, Arthur and Harold, on the assumption that as we already possessed cottages on either side of Alderside we would naturally be interested in the upkeep of the place. We would not need it ourselves, but father thought that we could make it available to other members of the family who did not have cottages, and wished to occupy it, or to others when no member of the family wanted it. The present owners have been most careful to follow father's wish. So the old place stands, needing each year some repair or improvement, but still delightfully homey and comfortable, still filled with the laughter of grown-ups and children, and still fragrant with memories that reach back to that famous night wnen the two lumber wagons drew up in front of the log cabin and the rain-soaked members of father's family first crossed its threshold. May it stand for many years to come. |

|

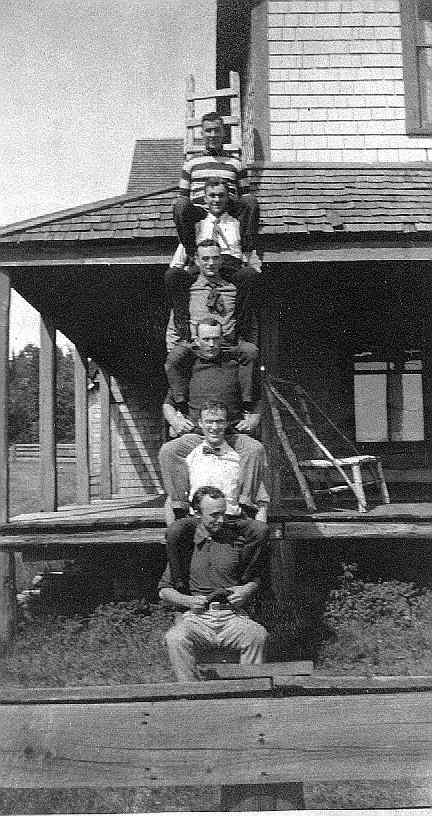

The six brothers at Alderside, before 1910. From the top down ---

This is the "Ladder" |

TO ALDERSIDEOur summer home at Dwight by the Lake of Bays - 1888 - 1959. I caught you in a pensive mood today, I, too, could think with you about the time And soon you blossomed like a maiden fair Then time wrought change; the pines rose strong and tall. O Alderside, dream on all winter through, H.S.S. September 22, 1958. 1) See 'Dwight Lore' for Norman's story of one of the events of that day of the great bee. 2) According to Alex one of the children did fall into the swamp, and the rules for revival were applied. He maintains that the rest of my story belongs to another occasion. According to my memory the story turns on the point that it was not a child crying that mother heard, but Mrs. Hood screaming as her fond husband thrashed her. Have it your own way! 3) See the binder in my series named Dwight Lore and Camping Trips. Arthur has here made a very careful list of trips, destinations, personnel, dates, and also of visitors at Alderside for the summers involved. |